I love studying cognitive biases and most of their names describe what they mean but these 25 are quite hard to identify because they are linked with the person who created them. See answers in the image.

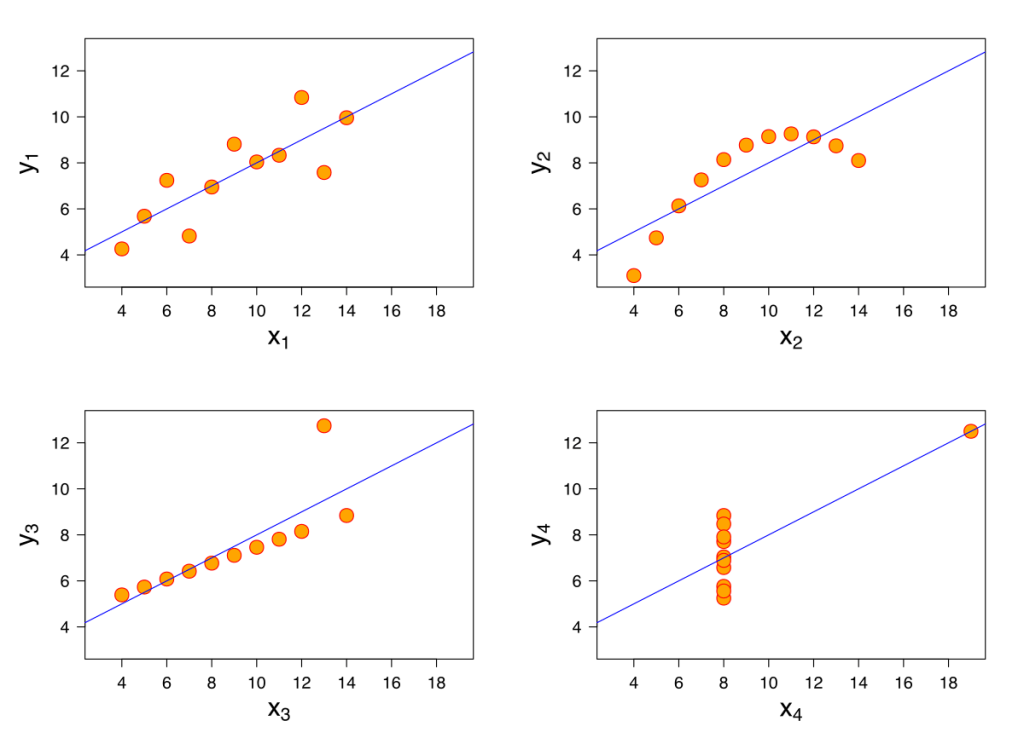

Anscombe’s Quartet: Four sets of numbers that look identical on paper (mean average, variance, correlation, etc.) but look completely different when graphed. Describes a situation where exact calculations don’t offer a good representation of how the world works.

Aumann’s Agreement Theorem: If you understand your opponent’s beliefs you cannot agree to disagree. If you agree to disagree it’s because one side doesn’t understand the other side’s view.

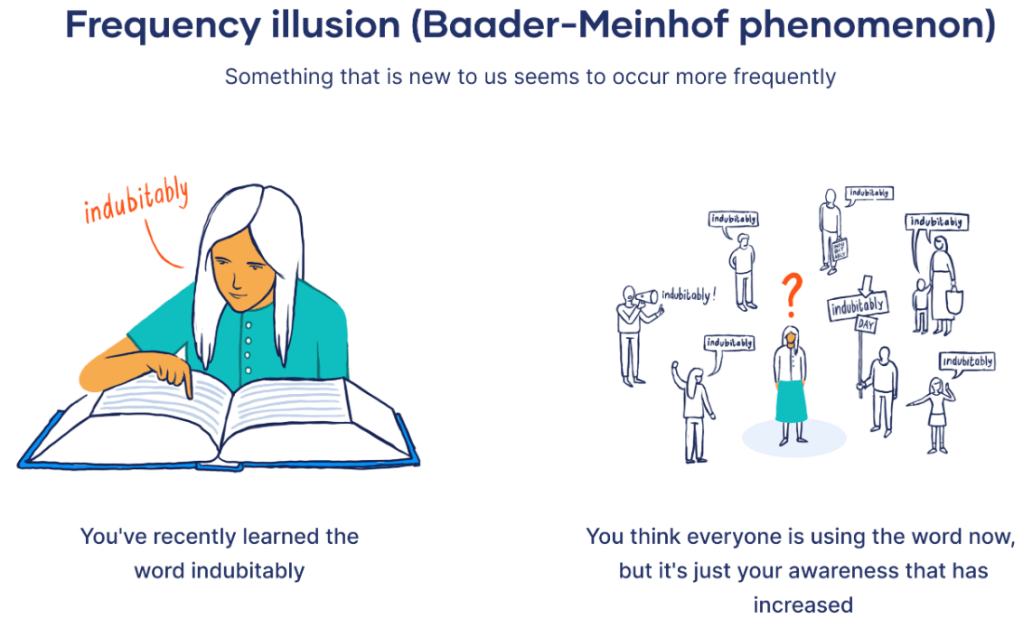

Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon: Noticing an idea everywhere you look as soon as it’s brought to your attention in a way that makes you overestimate its prevalence.

Ben Franklin Effect: Where a person who has performed a favor for someone is more likely to do another favor for that person than they would be if they had received a favor from that person.

Berkson’s Paradox: Strong correlations can fall apart when combined with a larger population. Among hospital patients, motorcycle crash victims wearing helmets are more likely to be seriously injured than those not wearing helmets. But that’s because most crash victims saved by helmets did not need to become hospital patients, and those without helmets are more likely to die before becoming a hospital patient.

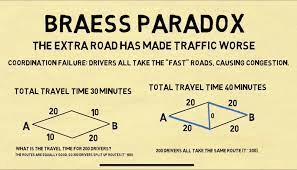

Braess’s Paradox: Adding more roads can make traffic worse because new shortcuts become popular and overcrowded.

Buridan’s Ass: A thirsty donkey is placed exactly midway between two pails of water. It dies because it can’t make a rational decision about which one to choose. A form of decision paralysis.

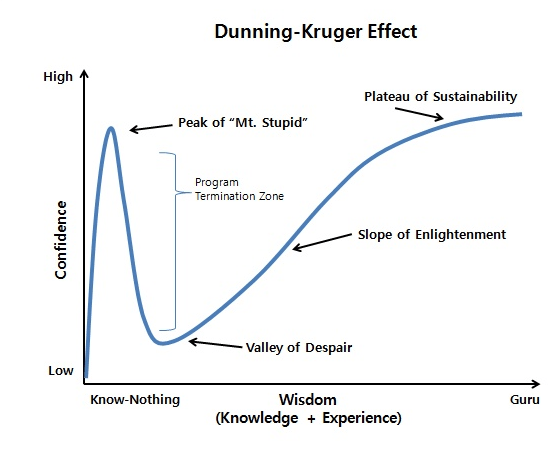

Dunning-Kruger Effect: Knowing the limits of your intelligence requires a certain level of intelligence, so some people are too stupid to know how stupid they are

Fredkin’s Paradox: Confronted with two equally good options, you struggle to decide, even though your decision doesn’t matter because both options are equally good. The more equal the options, the harder the decision.

Knightian Uncertainty: Risk that can’t be measured; admitting that you don’t know what you don’t know.

McNamara Fallacy: A belief that rational decisions can be made with quantitative measures alone, when in fact the things you can’t measure are often the most consequential. Named after Defense Secretary McNamara, who tried to quantify every aspect of the Vietnam War.

Pareto Principle: The majority of outcomes are driven by a minority of events.

Peltzman Effect: The reduction of predicted benefit from regulations that intend to increase safety.

Perky Effect: where real images can influence imagined images, or be misremembered as imagined rather than real

Planck’s Principle: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

Hanlon’s Razor: “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity.”

Hawthorne Effect: Being watched/studied changes how people behave, making it difficult to conduct social studies that accurately reflect the real world.

Peter Principle: Good workers will continue to be promoted until they end up in a role they’re bad at.

Ringelmann Effect: Members of a group become lazier as the size of their group increases. Based on the assumption that “someone else is probably taking care of that.”

Semmelweis Reflex: Automatically rejecting evidence that contradicts your tribe’s established norms. Named after a Hungarian doctor who discovered that patients treated by doctors who wash their hands suffer fewer infections, but struggled to convince other doctors that his finding was true.

Sturgeon’s Law: “90% of everything is crap.” The obvious inverse of the Pareto Principle, but hard to accept in practice.

Travis Syndrome: Overestimating the significance of the present. It is related to chronological snobbery with possibly an appeal to novelty logical fallacy being part of the bias.

Von Restorff Effect: That an item that sticks out is more likely to be remembered than other items.

Weber–Fechner Law: Difficulty in comparing small differences in large quantities.

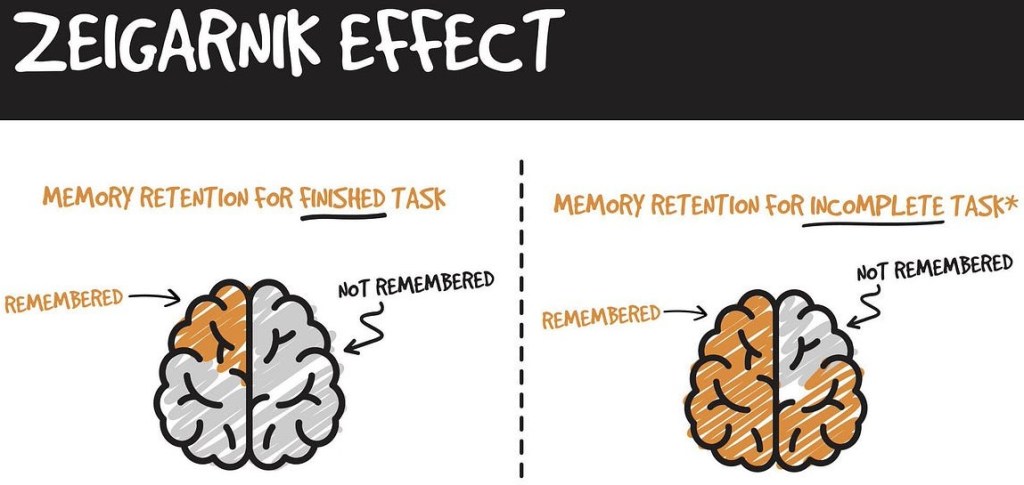

Zeigarnik Effect: That uncompleted or interrupted tasks are remembered better than completed ones.