From Chapter 9 of Adam Grant’s Think Again

One class is a lecture. The second is an active-learning session. In both cases the content and the handouts are identical; the only difference is the delivery method.

During the lecture the instructor presents slides, gives explanations, does demonstrations, and solves sample problems, and you take notes on the handouts.

In the active-learning session, instead of doing the example problems himself, the instructor sends the class off to figure them out in small groups, wandering around to ask questions and offer tips before walking the class through the solution.

At the end, you fill out a survey. In this experiment the topic doesn’t matter: the teaching method is what shapes your experience.

The data suggest that you will enjoy the subject more when it’s delivered by lecture. You’ll also rate the instructor who lectures as more effective—and you’ll be more likely to say you wish all your courses were taught that way.

Upon reflection, the appeal of dynamic lectures shouldn’t be surprising. For generations, people have admired the rhetorical eloquence of poets like Maya Angelou, politicians like John F. Kennedy Jr. and Ronald Reagan, preachers like Martin Luther King Jr.. It’s clear that lectures can be entertaining and informative. The question is whether they’re the ideal method of teaching.

In this experiment, the students took tests to gauge how much they had learned about the topic. Despite enjoying the lectures more, they actually gained more knowledge and skill from the active learning classes. Active learning required more mental effort, which made it less fun but led to deeper understanding.

For a long time, I believed that we learn more when we’re having fun. This research convinced me I was wrong. A meta-analysis compared the effects of lecturing and active learning on students’ mastery of the material, cumulating 225 studies with over 46,000 undergraduates in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Active-learning methods included group problem solving, worksheets, and tutorials.

Students scored half a letter grade worse under traditional lecturing than through active learning —and students were 1.6 times more likely to fail in classes with traditional lecturing. The researchers estimate that if the students who failed in lecture courses had participated in active learning, more than $3.5 million in tuition could have been saved. It’s not hard to see why a boring lecture would fail, but even captivating lectures can fall short for a less obvious, more concerning reasons.

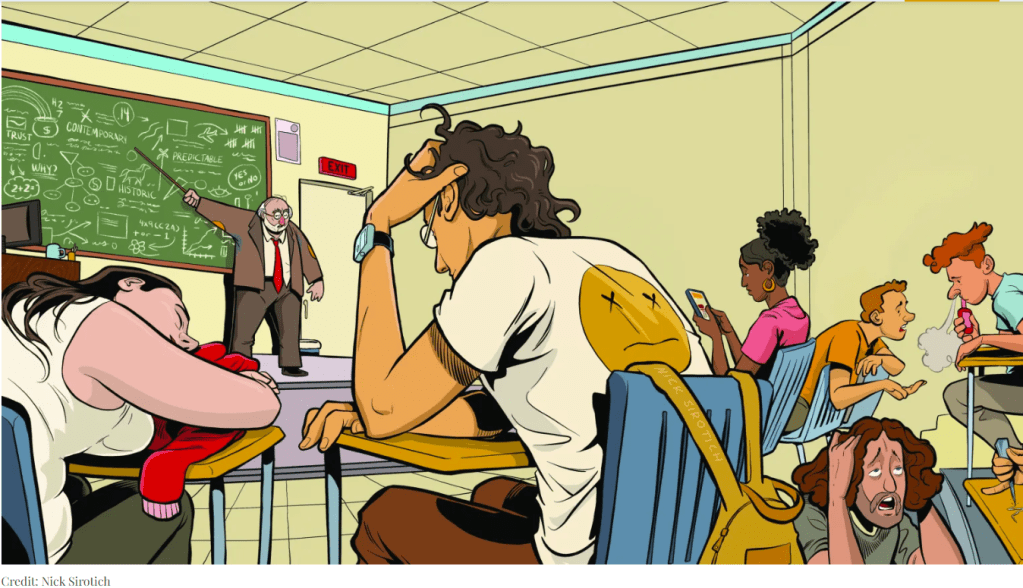

Lectures aren’t designed to accommodate dialogue or disagreement; they turn students into passive receivers of information rather than active thinkers. In the above meta-analysis, lecturing was especially ineffective in debunking known misconceptions—in leading students to think again. Experiments have shown that when a speaker delivers an inspiring message, the audience scrutinizes the material less carefully and forgets more of the content—even while claiming to remember more of it. Social scientists have called this phenomenon the awestruck effect, but I think it’s better described as the dumbstruck effect. The sage-on-the-stage often preaches new thoughts, but rarely teaches us how to think for ourselves.

Charismatic speakers can put us under a political spell, under which we follow them to gain their approval or affiliate with their tribe. We should be persuaded by the substance of an argument, not the shiny package in which it’s wrapped.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting eliminating lectures altogether. I love watching TED talks and have even learned to enjoy giving them. It was attending brilliant lectures that first piqued my curiosity about becoming a teacher, and I’m not opposed to doing some lecturing in my own classes. I just think it’s a problem that lectures remain the dominant method of teaching in secondary and higher education.

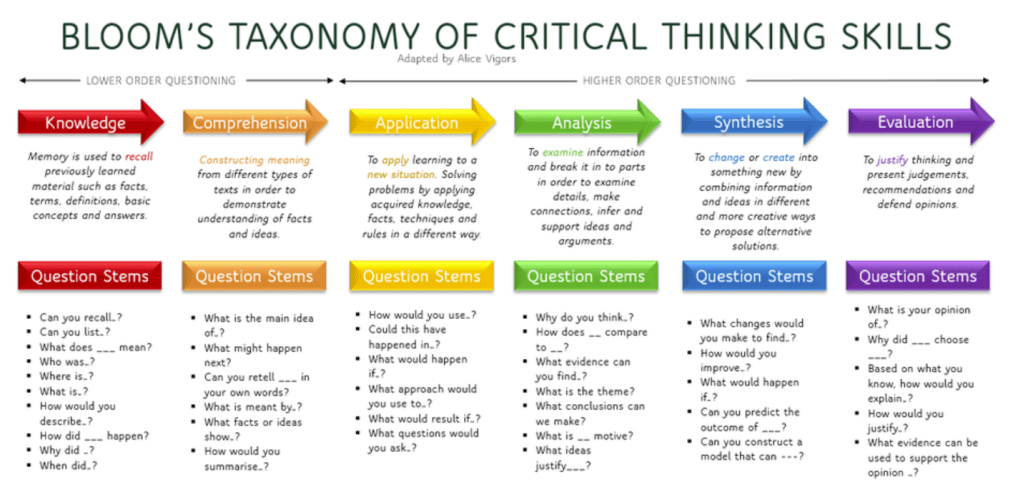

In North American universities, more than half of STEM professors spend at least 80% of their time lecturing and fewer than 20% use truly student-centered methods that involve active learning. If you spend all of your school years being fed information and are never given the opportunity to question it, you won’t develop the tools for rethinking that you need in life.