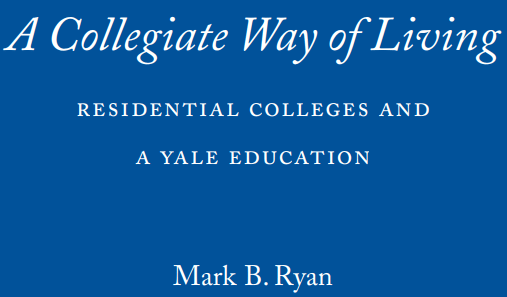

Taken from A Collegiate Way of Living, by Mark B. Ryan

Perhaps the earliest permanent residential college, still extant, was Merton of Oxford, founded in 1264 by the Bishop of Rochester to take care of the “temporalities,” as he said, of students. The buildings of Merton were grouped around a chapel, where students worshiped daily; its statutes, establishing the seminal “Rule of Merton,” prescribed diligence, sobriety, chastity, and other personal virtues. Merton and its early imitators were not teaching institutions, but with the founding of New College, Oxford in 1379, older fellows of the college began instructing younger ones. By the middle of the next century, the teaching functions at Oxford and Cambridge lay almost entirely in the hands of college lecturers. Unlike the university, the colleges governed student life beyond instruction: they attempted, we might say, to manage a student’s full development.

That was the model that the magistrates of Massachusetts Bay had in mind when they set out to build an institution “to advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity.” Some of the more practically minded observers suggested that the school simply hire ministers to read lectures, leaving the students to fend otherwise for themselves. But as Cotton Mather later retorted, “the Government of New England was for having their Students brought up in a more Collegiate Way of Living.” From that beginning in Massachusetts Bay, American higher education was concerned not only with the training of minds but also with the molding of character, and the “Collegiate Way of Living,” with its common residence, structured community life, intellectual exchange, and spiritual purpose and practices, was the path to those complementary goals.

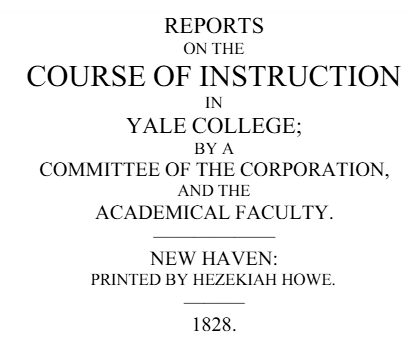

The focus of the seminal Yale Report of 1828 was curricular: it defended the classical curriculum—the study of what was called “the dead languages” and mathematics—as well as a prescribed, common study of other subjects chosen by the faculty. But it also defended the close community and residential arrangements of the traditional American college. The young students of that era needed, in the words of the report, “a substitute…for parental superintendence…founded on mutual affection and confidence” between students and their teachers. “The parental character of college government,” the report stated, “requires that students should be so collected together, as to constitute one family; that the intercourse between them and their instructors may be frequent and familiar.”

That goal, the 1828 report noted, required suitable residential structures and resident faculty who knew the students individually and well. These arrangements allowed not only for providing information to students through lectures—what the report called the “furniture” of the mind—but also for the “daily and vigorous exercise” of what it called the “mental faculties.” The aim of all this—both curriculum and college life—was “to lay the foundation of a superior education” and, as the report stated it, to “produce a proper symmetry and balance of character.”

The residential ideal was reinforced by an American habit of placing these schools in rural settings—often in towns with names such as Athens and Oxford—away from the temptations of the cities, where other living arrangements would have been available.

A leading figure in that revival of residential colleges in the 1910s was Woodrow Wilson of Princeton. As university president, he spoke of the need to join “intellectual and spiritual life” and to “awaken the whole man.” Princeton, he said, was “not a place where a lad finds a profession, but a place where he finds himself.” Wilson moved Princeton away from the free elective system back toward a more structured curriculum; and with the construction of residences, he attempted to rebuild the sense of community that he thought the university had lost. “The ideal college…,” he said, “should be a community, a place of close, natural intimate association, not only of the young men…but also of young men with older men…of

teachers with pupils, outside of the classroom as well as inside of it.”

For architectural inspiration, Wilson looked back once again to the English residential colleges with their closed quadrangles. Hiring Ralph Adams Cram,

preeminent spokesman for the revival of the English Gothic style, as Princeton’s supervising architect, Wilson hoped to create an entire system of residential quadrangles, each with a dining hall, common rooms, and a resident master. His notions culminated in the design and construction of the Graduate College, but he failed to win support for his larger vision.

The fulfillment of Wilson’s vision for a lasting and comprehensive system of residential quadrangles took place not at Princeton: it awaited the philanthropy of Edward S. Harkness, Yale Class of 1897, who in 1926 proposed to fund such a system at his alma mater. Yale was slow to respond with a plan, and the delay tried the patience of the donor, who began to feel that Harvard might prove more fertile ground for his generosity.

Harkness made the same proposal to Harvard’s President, who snapped it up, calling it “a bolt from the Blue.” After the announcement, a Yale undergraduate magazine referred to the scheme as “a Princeton plan being tried out at Harvard with Yale money.” Harkness then reconciled with his alma mater and agreed to fund what was called the “Quadrangle Plan” at both schools.

Officials from both Harvard and Yale then went scurrying across the Atlantic to examine the Oxbridge colleges on which their new units were supposedly to be modeled. But what they needed to build, of course, was something quite different. The British colleges were autonomous sovereignties, self-governing and independently financed agents of instruction with their own faculties. The American units, grafted onto an existing, centralized university, would be something new, something between a British college and an American dormitory.

The collegiate ideal also accepts the principle that students educate each other fully as much as they are educated by the faculty. They may absorb information in the classroom, but it is in exchanges with one another that students internalize that information, take the measure of what rings true, relate it to their experience and intuitions, and assess how it has meaning in their lives.

The second enduring element in the collegiate ideal is that it attempts to look after the whole student psyche, to promote the development of character as well as intellect. That is a persistent theme, from the Yale Report’s psychological portrait of the student to Woodrow Wilson’s concern that a Princeton student find not a profession but himself.The college must seek to create an atmosphere in which students are supported in their full personal growth. The college community supports that growth by serving as witness to it, by appreciating it, by providing a forum in which all student concerns—especially personal and developmental ones—can be given a full hearing. For college officers, this implies that what we might call human sensitivity is every bit as important a credential as scholarly achievement. College officers should be skilled as personal counselors, and they have an obligation to familiarize themselves with the major issues of personal development in the college years.

College officers should be skilled as personal counselors, and they have an obligation to familiarize themselves with the major issues of personal development in the college years.

A traditional element in this focus on character in the collegiate ideal is an emphasis on values we call moral and spiritual. Obviously, that does not mean for us what it meant for Cotton Mather, but their meaning for us lies in community ethics and in personal awareness. Ethical concern should be at the heart of the college’s community life. In their interactions with each other, in the creation and enforcement of college regulations, students must constantly be encouraged to look to the community’s harmony and welfare and to consider how the virtues and values that thus come to play are expressed—or not expressed—in the larger society.

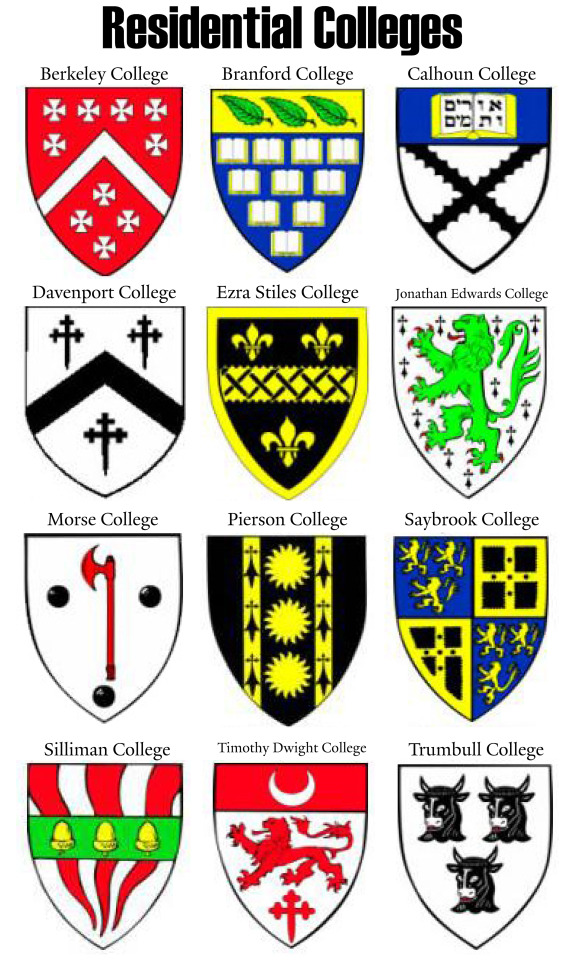

Even though campus-wide mandatory chapel ended at Yale in 1926, it was that same year when the benefactor Edward Harkness commissioned James Gamble Rogers to create a whole system of intimate communities—residential colleges—inspired by those of Oxford and Cambridge. In these small communities, despite the growth of student numbers Yale would continue to cultivate those ancient ideals of collegiate living: ideals such as ethics, character, citizenship, friendship, and learning from one’s peers. Yale’s residential colleges have since become models for residential systems or units established at universities across the United States and beyond.

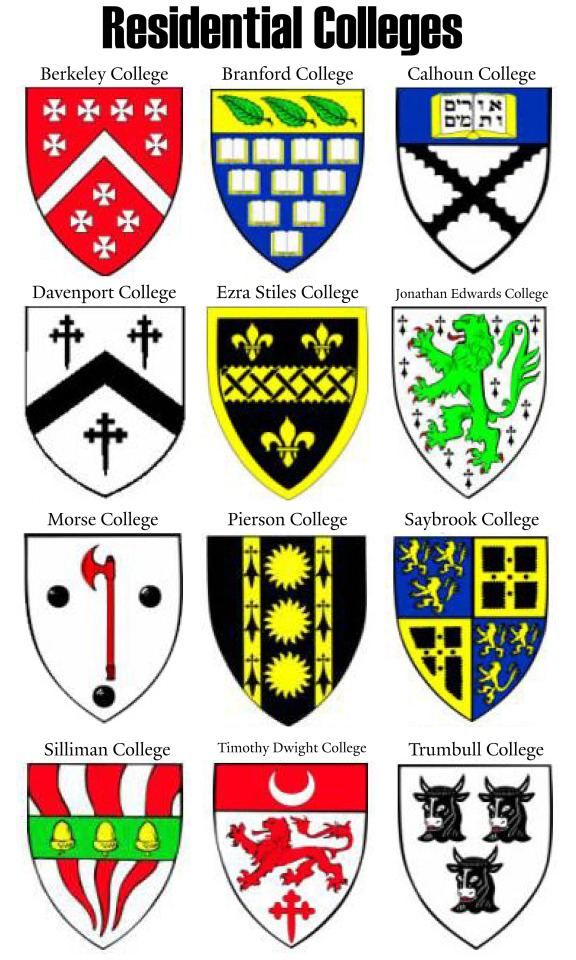

Jonathan Edwards was among the first seven of Yale’s colleges, which opened their doors in the fall of 1933. The original plan called for ten such colleges: the eighth opened the following year, the ninth a year after that, and the tenth in 1940. Two additional colleges were built in the early 1960s. Each of these units counts around 400 to 450 undergraduate members, over 80% of whom are in residence. Students are assigned to the colleges shortly after their acceptance to the University, and before their arrival. All are made members of a college; no undergraduate students at Yale are unaffiliated with the system.

So that the students might be exposed to the full range of the backgrounds and interests of their peers, the membership of each college is intended to be roughly a microcosm of the entire student body. From the time of their arrival, they are fully members of their residential colleges: they take many of their meals in the college dining hall, participate fully in the college organizations and student life, and fall under the authority of the college administrators. Although policy allows students to transfer from one college to another, few do so: the vast majority maintain their original college affiliation throughout their four undergraduate years.

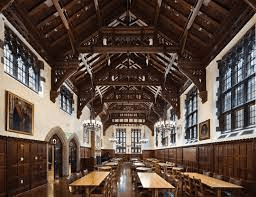

The Yale residential colleges are quadrangular in form, built around a landscaped courtyard; and it has as its focal interior space a large dining hall, which in this case is modeled after an Elizabethan banquet hall, with a soaring, beamed and gabled ceiling, a balcony, and two large stone fireplaces. Referred to in J.E. as the Great Hall, that space serves not only for dining, but for concerts, theater performances, dances, and other festivities.

Also like the other colleges, J.E. is equipped with a sizable common room, for socializing and smaller assemblies, and with a senior common room for the fellows’ meetings and dining. A junior common room serves as an additional, relatively intimate dining and gathering space. The college has two libraries, both serve as study and meeting spaces. The college houses three classrooms, about a dozen faculty offices, and five pianos (including one concert grand, for performances in the Great Hall). In its basement are numerous student facilities, including a computer room, a kitchen, a squash court, exercise rooms, a game room, a television room, a student-operated buttery, and such specialized facilities as music practice spaces, a darkroom, a woodshop, and its own letterpress print shop. The spacious, three-story master’s house is suitable for entertaining sizable groups of students and faculty; and the faculty apartments, with their large living rooms, are agreeable and roomy enough for both family life and entertainment of students.

Almost from the moment of their arrival, Yale students identify with their respective colleges. The vitality of their community life is expressed in numerous college organizations: student governments, intramural sports teams, music and drama groups, and committees dealing with social life and educational matters. A handful of residential college seminars—chosen by student committees—add a specifically academic component to college life. They are taught in the college’s classrooms, and the college’s students have priority in enrollment. The colleges, however, are social institutions. They are not identified with an academic field, and although the intellectual engagement that they promote is a vital part of Yale life, it is co- or extracurricular. The colleges are centers of academic counseling; they other tutoring programs in writing and sciences and some noncredit, academically oriented programs such as senior essay workshops overseen by fellows. Prominent visitors occasionally deliver college-sponsored lectures or, more frequently, join in informal discussions at teas in the masters’ living rooms. The dining halls and common rooms become the setting for plays, concerts, and other cultural events, often involving student performers.

The tradition of liberal learning has always viewed higher education as more than training for the marketplace, and the residential principle assumes that it is more than a training of intellect. A university exists to promote conversation—between generations, among teachers, and among students. Residential colleges form communities within the university, where the generations come together, where teachers of various disciplines converse with one another, and above all, where students freely mix with and learn from one another, over time—sharing their experiences, explaining their interests, inspiring one another with their enthusiasms. These social interactions, intensified by that “shared spirit and energy,” help to stimulate the conversations that are the soul of a university. At the same time, the college’s responsibility for student welfare, and the needs and arrangements of organized institutional life, assure that the university attends to the students’ personal as well as intellectual development.

Surveying “living-learning communities” throughout the United States, Terry Smith has remarked that “Yale’s is surely the archetypal residential college system in North America.”