Taken from A Collegiate Way of Living by Mark B. Ryan

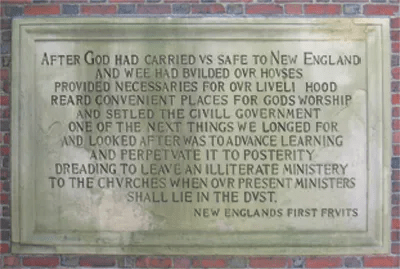

“The two colonial colleges of New England were founded by a very specific and peculiar religious sect, British protestant Calvinists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries— Puritans, they were called. Whatever its virtues and failings, that tradition lent itself powerfully to promoting higher education. We begin this story with the unpleasantry of looking northward (from Yale), to Massachusetts. Listen to one of the most extraordinary statements of the American colonial experience, written by Henry Dunster, the first president of Harvard, in 1643:

After God had carried us safe to New England and wee had builded our houses,

provided necessaries for our livelihood, rear’d convenient places for Gods worship,

and settled the Civil Government: One of the next things we longed for, and looked after was to advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity; dreading to

leave an illiterate Ministry to the Churches, when our present Ministers shall lie in the dust.

“To advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity.” Imagine that as a priority, in those circumstances: a struggling colony in what seemed a wilderness, only 10 years old, with a total population of only ten thousand, barely having built basic shelter, its very survival always under threat—and in an era when, even in Britain, only a scant few attended a university. The key reason they felt that need was that the Puritan religion, and its form of worship, were textbased.

The main task of Puritan ministers—unlike priests and shamans in more

ritualistic religions—was to expound on scripture, and they could do that well

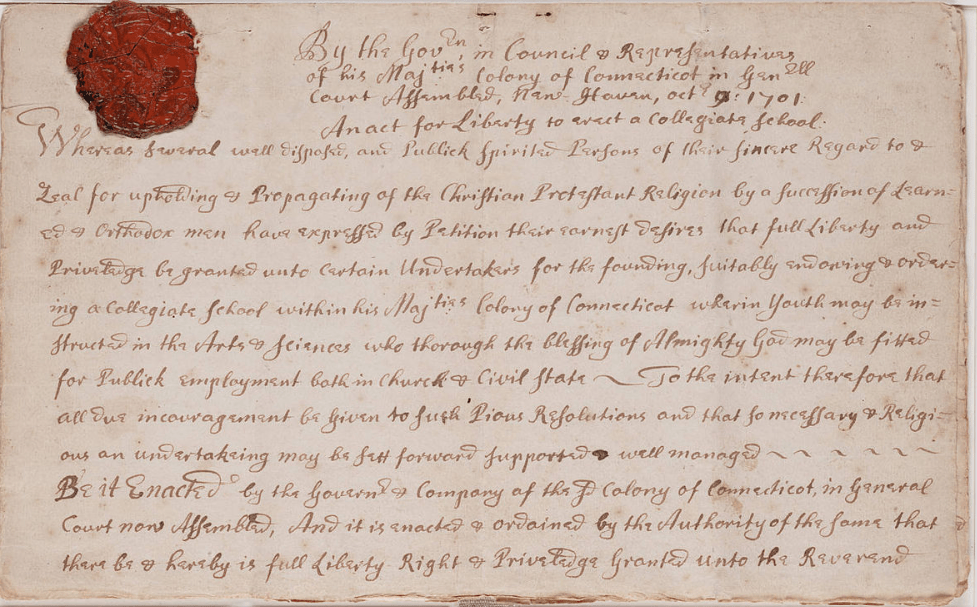

and correctly only with sophisticated learning and trained minds. The founders of Harvard and Yale shared many assumptions about education beyond this sense of its necessity. Their ideals can be traced back through the medieval universities of Europe to the academies of Greece and Rome. The classical world had developed the notion of liberal education—an education for the liber, the free citizen-intended both to transmit a cultural heritage and to inculcate a general intellectual competence and personal virtue or character. By Roman times, the means of doing this was seen as training in the seven liberal arts: grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, astronomy, geometry, and music. Those arts, the Puritans still believed, were proper training not only for ministers, but for secular leaders as well. As Yale’s founding charter put it, this was to be a place “wherein Youth may be instructed in the Arts and Sciences…[and] fitted for Public employment both in Church & Civil State.”

The Puritans had one other notion that turned out to be crucially important for the history of American higher education. “It is well known,” stated Harvard’s governing board in 1671,“what advantage to Learning accrues by the multitude of persons cohabiting for scholasticall communion, whereby to actuate the minds of one another, and other (ways) to promote the ends of a Colledge Society.” The simplest way to “instruct youth” would have been to hire instructors, maybe rent or build some lecture rooms, but otherwise let the students make their own way in the town, living wherever they might. That was the way it was often done on the European mainland and in Scotland.

But the Puritan magistrates wanted a residential college, where students learn together by living together. This was an especially English ideal, realized in the colleges that made up the universities at Oxford and Cambridge. There, students studied, lived, and worshiped in communities with their teachers—and they would do the same at Harvard and Yale. In that way, education became not merely a training of mind or a preparation for profession, but a comprehensive experience meant to develop character, to develop the whole human being in all its dimensions- intellectual, moral, personal.

With this place established up north, then, why was Yale necessary at all? People in Connecticut wanted their own college; but more than that, they grew convinced that up there in Cambridge the job had been botched. Listen to the Rev. Solomon Stoddard, preaching a sermon in 1703: Harvard, he said, was a place of “Riot and Pride…profuseness and prodigality…[It is] not worth the while for persons to be sent to the Colledge to learn to Complement men, and Court women.”

In case you didn’t get that 17th century rhetoric, Harvard, he said, was out of control. Around the Yard they were listening to noxious characters like Episcopalians and showing far too much tolerance for non-Calvinist teachings. So in 1700, ten ministers gathered in Branford, Connecticut, to talk about founding a new college. Most of them were disgruntled Harvard alumni who, like alumni everywhere, thought their school had gone to the dogs since their own graduation. The Collegiate School, as it was called, was launched in 1701 with a charter granted by the colony’s General Assembly, and with the intention to turn out “a succession of Learned and Orthodox men.”

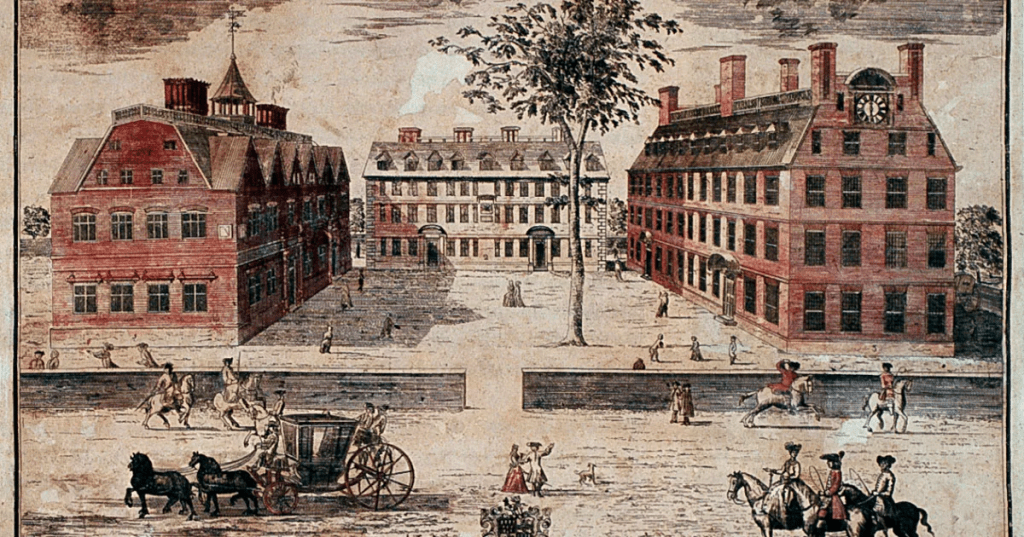

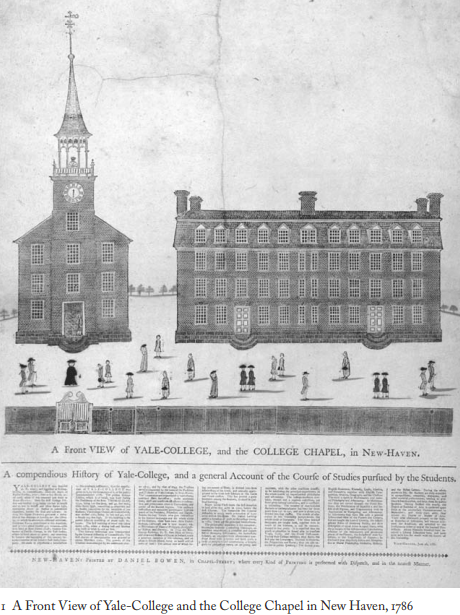

In 1717, the school acquired this site by the green in New Haven, then a town

of just some 1,000 souls. It gave the name Yale College to the first building it

erected there, in gratitude to a benefactor with an exceedingly good sense of

timing. Through mere usage, the name soon got transferred from the building

to the school itself. In the middle of the eighteenth century the college added a more substantial brick structure, Connecticut Hall, which still stands as the

oldest building on campus. Shortly thereafter a chapel went up beside it.

There would have been 25-30 boys, as the entering age was typically about 15 or 16 years old. The entire student body would have numbered something over 100, and the faculty would have consisted of the president, one or two other professors, and three or four junior tutors. To be admitted, you would have had to pass an oral entrance exam, in front of the president, showing that you knew Latin and basic Greek, as well as rules of arithmetic. Not only were you to know Latin, mind you: it was the language of the College. You were expected not only to read your textbooks in it, but to speak it, both in and out of the classroom. Use of English was originally against College regulations, although we can’t say how well that was observed. The requirement that students study Latin, by the way, lasted well into this century. In the 1920s, the Faculty almost abolished it; but the University’s most eminent alumnus, former president William Howard Taft, who was on the Yale Corporation (the Board of Trustees), declared, “Over my dead body!” Taft had foresight. He died in 1930. The Latin requirement went with him in 1931.

For all four years, at colonial Yale, you would have studied exactly the same things, together; and together you would have gone through the rituals of daily prayers and readings from scripture. You would have heard lectures, but you also would have engaged in things called recitations, disputations, and declamations. A recitation was a parroting back of what you had memorized in a textbook; a disputation was a debate, in which you showed your command of the material by taking one side or another of a proposition, arguing for or against it according to the prescribed rules of logic; and a declamation was an oration, a lecture of your own that you embellished with the tropes of formal rhetoric. It was a far more oral form of learning than we have today, emphasizing memorization and eloquence.

The use of Latin shows another basic notion in the colonial New Englanders’ concept of education. Their intention was not only to inculcate protestant orthodoxy, but to perpetuate the intellectual tradition of Europe, with its grounding in the classics. What you studied at Yale and Harvard was basically the same as what you would have studied all over Europe: the seven arts, some classical literature, plus what was known as the “three philosophies”—natural philosophy, ethics, and metaphysics. The Puritans saw no tension between promoting religious orthodoxy and perpetuating classical learning; in fact, they saw them as necessarily going together. In their view, classical learning prepared the way for Christian truth. To bring that truth to America, they had to bring the learning.

It is all nicely symbolized in the two compatible buildings—college and

church. But in fact, there was a tension there, because in the intellectual culture of Europe, those arts and philosophies were always growing and changing. Soon their growth began to threaten the orthodoxy; eventually, it threatened classical learning itself. There was a built-in tension between the Puritan goals of advancing learning, and perpetuating it to posterity.”