Sallie McNeill A Woman’s Higher Education in Antebellum Texas, Rebecca Sharpless in Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives

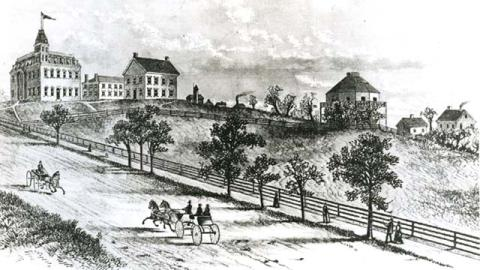

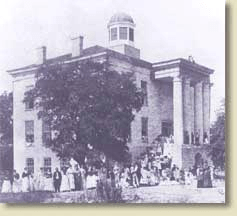

“In December 1858, eighteen-year-old Sallie McNeill and her thirteen classmates received diplomas from Baylor University. The flowers of plantation society, these young graduates were about to scatter from Baylor’s hilltop campus in the hamlet of Independence, in Washington County, to their homes across Texas. Almost all would soon become wives and mothers; none would put her education to use in the public sector. Yet Baylor was much more than a finishing school for the wealthy. McNeill and the other young women had studied mathematics, natural sciences, literature, and languages; had published their words in the college newspaper; and had defended their learning in a series of oral examinations before panels of distinguished men and the interested public. At graduation, each student read aloud her commencement address. McNeill’s experience at Baylor suggests that this rigorous education was something more than a frivolous indulgence for wealthy southern belles.

McNeill, bookish and introspective, recorded in her diary her impressions of her two years at Baylor and the nine years following, until her death in 1867 at the age of twenty-seven. Her entries give insight into the dilemma of education for women in antebellum America, particularly in the South: What should women be taught, and how should they use what they learned? McNeill was the granddaughter of Levi Jordan, a very wealthy sugar planter in Brazoria County, and she represented a class of women whose lives of privilege were built on slavery. But she was also a voracious reader who loved the life of the mind, and her college education fed and encouraged her intellectual enterprises…

As in other schools in the South, each term at Baylor ended with oral examinations before a panel of outside questioners, and the examinations were open to the public. The panel for 1858–59 consisted of twelve men from throughout Texas, including three ministers, two medical doctors, and three attorneys. Thus, young women performed in public, judged by adult men. Harris remembered, “How we trembled in our shoes as we took our seats in front of them.”

Some parents, fearing the stress of the examinations, apparently withdrew their daughters before the pressure built, prompting a sharp order in the 1857 catalog: “The practice of indulgent parents in removing pupils from the Institution before the close of the session to avoid these exercises cannot be too [earnestly?] reprehended . . . In future no young lady can thus leave without the consent of the Principal; nor can she resume the position in her class.” Perhaps parents withdrew their daughters because of fear that the stress would prove harmful, or perhaps they simply had low expectations for their daughters’ attainments. The women’s instructors clearly clashed with the parents in either case.

Two months after her senior exams, McNeill described them in her diary: “Well, the long expected and anxiously looked for, yet dreaded day arrived, on the whole our school acquitted themselves creditably, Mr. Kemble (one of the board of Examiners) came with the expressed determination to tease & make us miss as he did the boys, especially in Latin. He succeeded in puzzling – and [all] afternoon worried us with his simple questions. Becca missed, Rach & myself guessed through. He is very ungallant to Ladies.

”Family members, townspeople, and alumnae from near and far attended the examinations. Margaret Lea Houston, who lived across the road from the women’s college, wrote to her husband, U.S. Senator Sam Houston, in December 1853, “The examination came off last week, and although we have had bad weather a part of the time, it was really a grand affair. We had a house full of visitors all the time, and every body else who entertained company seemed to have quite as many, and all seemed greatly delighted with the attainments of the students.”

For the first five years of Baylor’s existence, the male and female departments shared a faculty, which in 1850 consisted of five men and Louisa Buttlar, who taught music and embroidery. In June 1851, however, as Rufus Burleson’s decree divided the male and female campuses, two separate faculties arose.

At Baylor, most of the female students lived in a boardinghouse maintained by Martha Clark, with as many as four to a room. The college administration devised rules to attempt to keep order, while the young women strove to make their living space as flexible as possible. They were constrained to “occupy the Rooms assigned them” and forbidden to leave the college grounds without permission.

When the class of 1858 dispersed, McNeill returned home to the plantation,

about a hundred miles and a day’s journey from Independence by rail and stagecoach. With a widowed mother and a domineering grandfather in the person of Levi Jordan, she felt she had little choice. Two months after her departure, she questioned her years at the university, despite sprinkling the French she had learned there in her musings:

Two years have I spent at Baylor University and now with a Diploma, testifying my education to be completed, I am again a la maison, quietly endeavoring to instruct my little school, composed of three boys and two girls. Whether my efforts will prove satisfactory to them or myself, the future alone will reveal. How little good have I done in the world. My friends do not say so, but I feel my deficiencies. Kept at school all my life, and treated as a child, with nothing but books to employ my thoughts, it is not strange that I should be indolent and idle. I am a child still, dependent on others.

Despite the growing numbers of American females who worked as teachers

in the middle of the nineteenth century, Baylor women eschewed the classroom. Teaching attracted primarily middle-class women, and Baylor alumnae came from the upper echelons of Texas society. McNeill was the only one of her peers who became a teacher during the antebellum period, and she taught only on her home plantation, with her younger siblings as her pupils.

McNeill’s life came to an abrupt end, likely from yellow fever, on October 28. She was twenty-seven years old.