Taken from Oriard, M. (2014). Chronicle of a (Football) Death Foretold: The Imminent Demise of a National Pastime?. International Journal of the History of Sport, 31(1-2), 120-133. Michael Oriard, was a walk-on player for the University of Notre Dame and then played for four seasons as an offensive lineman for the Kansas City Chiefs.

After retiring from football, he earned his PhD at Stanford and became a professor and later Associate Dean at Oregon State University. He has written 8 books about sports, 6 about football.”

“Unlike soccer and rugby, the two versions of football most available to American collegians in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, American football is fundamentally a collision sport. Initially that aspect of the game was an accidental consequence of rules with other purposes, and the stages by which this happened are familiar to football historians:

The transformation of English rugby into American football was then due to the influence of Yale’s Walter Camp, beginning with two decisive rules, in 1880 and 1882: first, assigning the ball to one side at a time, instead of putting it in play through the rugby scrum; then, requiring the team with the ball to advance it five yards, or lose ten, in three tries.

It appears to have been wholly unintentional that Camp’s new rules also made American football a collision sport. The scrimmage line separated the teams into two sides, facing off for combat. Hammering the ball into the middle of the line with power and bulk became more effective. Camp proposed this change, and his colleagues accepted it, undoubtedly without foreseeing all of the consequences. By 1888, American football had become a game of blocking and tackling, as legendary Green Bay Packer coach Vince Lombardi would still be describing it 80 years later.

While American football became a collision sport not altogether by intention, it was embraced, by both players and spectators, not despite the resulting violence but to a considerable degree because of it.

Football’s violence always provoked concern, but that concern was always countered by celebrations of the manly courage and vigor that the game required. For many commentators, the bruises and broken bones that resulted from the brutal give-and-take within the rules were acceptable, even welcome, however much denounced by others.

No consensus on the boundary between necessary and unnecessary roughness, and how to preserve the one but eliminate the other, was reached in the 1880s and 1890s, or any time since. A selective survey of the newspapers of the 1880s and 1890s, with sensationalized images of carnage and mayhem, might suggest that football was irredeemably brutal.

But these images and stories appeared alongside others that conveyed a very different sense of the violent game: the players were heroic, larger-than life, the descendants of Greek heroes and Roman gladiators. The violence of football was essential to its heroism. And defenders of the sport often identified “newspaper sensationalism,” not the violence itself, as the new game’s greatest problem. Newspapers competing for circulations by ratcheting up their sensationalism—as they did with crimes and natural disasters and political chicanery—exaggerated football’s dangers to thrill their readers.

In an unusual twist for Americans typically ignorant of their own history, the story of President Theodore Roosevelt’s intervention in the football crisis of 1905 has entered popular consciousness in discussions of football’s current crisis over head trauma. The game was so brutal in its early years, the usual telling goes, that President Roosevelt himself had to step in to make it safer and save it.

But Roosevelt valued the game’s legitimate violence enormously. As he told Harvard’s graduating class in June 1905, in words that would be quoted repeatedly during the following football season, “I believe heartily in sport. I believe in out-door games, and I do not mind in the least that they are rough games, or that those who take part in them are occasionally injured. I have no sympathy whatever with the overwrought sentimentality which would keep a young man in cotton wool, and I have a hearty contempt for him if he counts a broken arm or collar bone as of serious consequences, when balanced against the chance of showing that he possesses hardihood, physical address, and courage.”

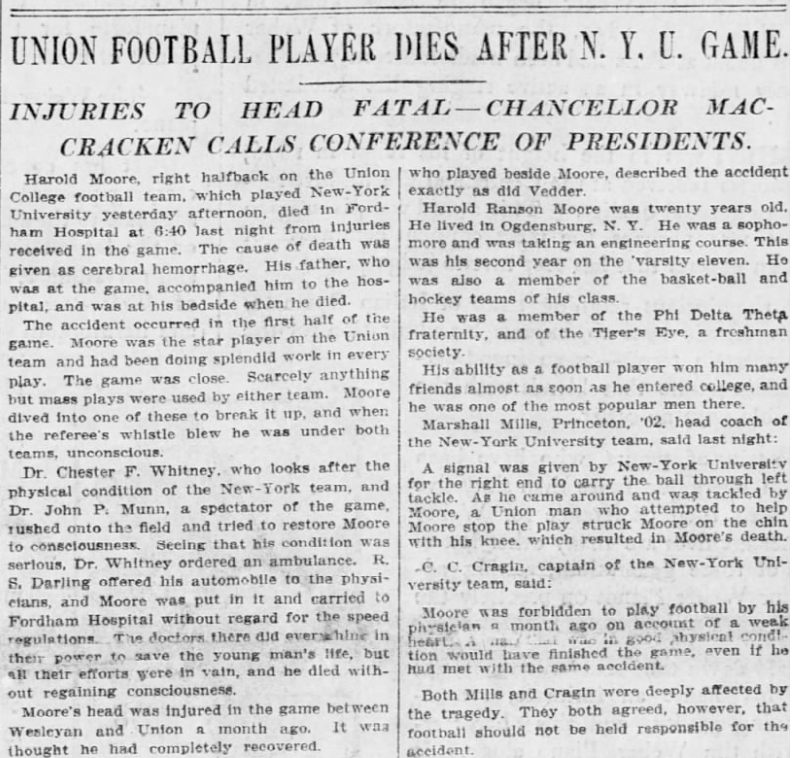

When the new season opened with the usual carnage, Roosevelt summoned the football leaders of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton to the White House. After he won their pledge to make the game safer, the press celebrated the President with his Big Stick as a tamer of the football slugger. This historic meeting actually might have had no impact at all had Union College’s Harold Moore not been killed in a football game played against New York University a month later. The immediate actions taken by NYU’s chancellor and Columbia University’s president, not Roosevelt’s intervention, led to the revision of the rules that “saved” football, and to the creation of the NCAA to oversee the game.

The crisis of 1905 did not turn the public against the violence of football. Rather, it resulted in yet another, neither the first nor the last, attempt to make football safer but not too safe. What made football violent, after all, was what made it heroic: football built character through testing the players’ physical courage and manly forbearance. A cover of the humor magazine Judge in the spring of 1906, as various institutions and organizations were hammering out new rules (most importantly, legalizing the forward pass), perfectly captures the competing values and the dilemma facing those who would make football safer. Titled “Football in 1906 Under the New Rules,” the cover shows two beribboned and top-hatted fops, one in pink (for Harvard’s crimson) and looking a lot like the President, a Harvard grad, the other in powder blue (for Yale), doffing their hankies and bowing to each other before the start of the game. On the field lies a list of the game’s new rules: “No Pinching,” “No Slapping,” “Hug Easy,” and so on. Football was the manliest of American sports, and any hint of emasculating it raised alarm or derision.

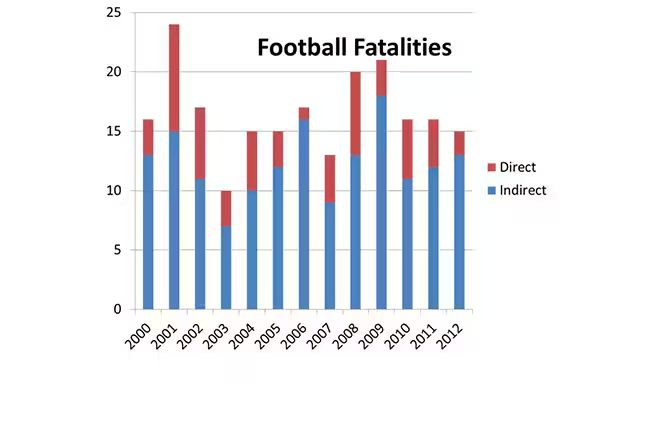

The new rules made the game only marginally less violent. After 18 died from injuries in 1905, the death toll dropped to 11 in 1906, and the same number in 1907, then climbed to 13 in 1908 and jumped to 26 in 1909, prompting the next crisis. Football’s death toll before 1931 has been documented from reports in the New York Times and other newspapers. In 1931, the American Football Coaches Association began tracking deaths and serious injuries more systematically: 31 fatalities in 1931, 24 in 1932 and 1933, 23 in 1934, 28 in 1935, and so on.

The provocation to begin tracking them in 1931 was the death of Army Cadet Richard B. Sheridan, from a broken neck suffered in a game against Yale, played again in front of sportswriters from the leading New York newspapers. This time, unlike in 1905, what’s remarkable is the absence of a resulting crisis. A flurry of articles followed on football’s dangers and making the game safer, but nothing much happened, and for this I would offer two primary reasons: first, football by this time had become too important to too many individuals and institutions in too many ways to be radically changed, let alone abolished; and second, among those institutions was the popular press (newspapers and magazines), plus the new media of radio and film. By 1931 the media depended on football (and other sports) as much as football (and other sports) depended on the media. Unlike the sensationalizing and muckraking press in the 1890s and early 1900s, the media in 1931 covered the tragedy of Cadet Sheridan’s death for a day or two, then returned to the business at hand, the big national games and local contests coming up the following Saturday.

Americans in the 1930s still wanted their football violent, just not too violent. “Football” in this era, and into the 1950s, meant predominantly college football on the national level, with the high school game ruling locally and the professional game barely registering in public consciousness. No one cared about pro football outside the handful of large cities that had NFL franchises until the 1950s, when television made it possible for the pro game to reach a national audience. TV was essential, but the terms on which the professional football was embraced in the late 1950s and 1960s were deeply connected to the game’s necessary violence.

Pro football into the 1950s was widely regarded as merely brutal and mercenary, without the compensating values of school spirit and character-building. A story in Life magazine in 1955 titled “Savagery on Sunday” and featuring several photographs of slugging and other dirty play captures this viewpoint. (Beginning to worry about its national reputation with the coming of television, the NFL sued the magazine.) Just a few years later—notably in the season immediately following the 1958 NFL title game that is widely viewed as marking pro football’s ascendance to national prominence— sports journalists were still describing pro football as brutal but, in a remarkable reversal, brutal now in a way that compensated for the softening and deadening routines of postwar American life. “Savagery on Sunday” in 1955 became “sanctioned savagery” in 1959, “an escape from or a substitute for the boredom of work, the dullness of reality,” in the words of Thomas Morgan in Esquire magazine. Over the next few years other magazines celebrated “The Controlled Violence of the Pros,” “Madness on Sunday,” and “Sunday’s Gladiators,” while television added special programs on “The Violent World of Sam Huff” (CBS, 1960) and “Mayhem on a Sunday Afternoon” (ABC, 1965).

Pro football went from near-dismissal in the early 1950s to Americans’ favorite spectator sport in a Harris poll in 1965. From the 1960s into the second decade of the twenty-first century, the routine and sometimes spectacular violence of pro football has been central to its popularity and cultural power.

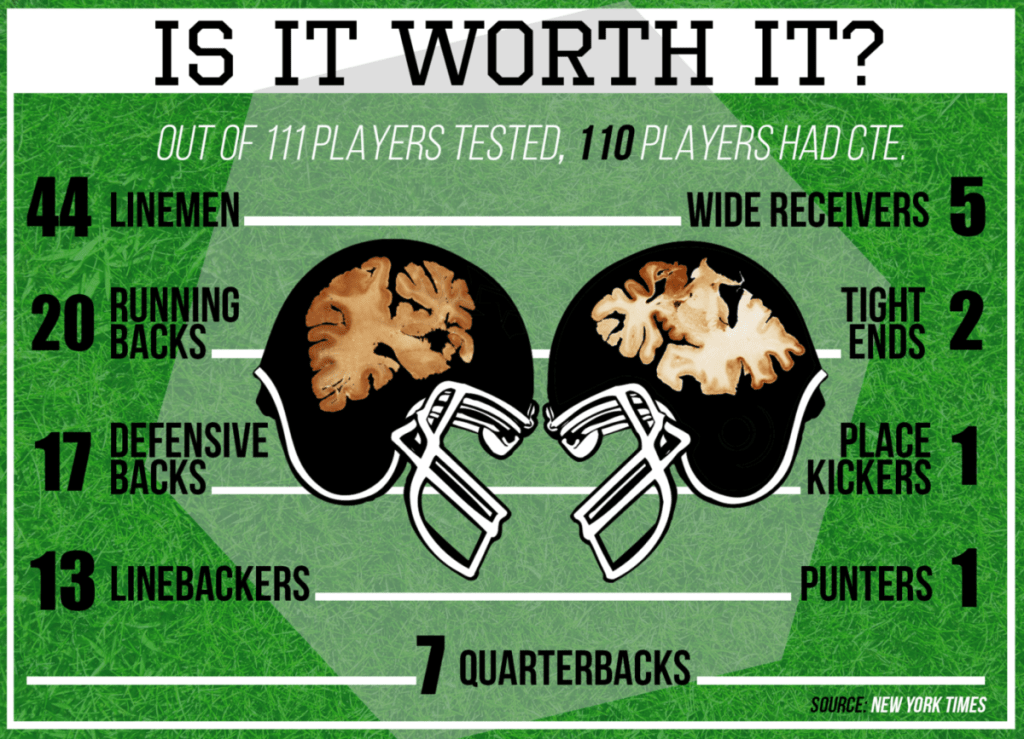

Football’s violence always had consequences, but popular understanding of those consequences was only anecdotal—the once all-pro fullback who was now too crippled to run on the beach with his kids—until the 1990s, when surveys of former players began suggesting that mildly or severely crippled bodies were the norm rather than the exception. But the crippled former players invariably said that the cost was worth it, and that they would unhesitatingly do it again. The football-loving public had no compelling reason to feel very bad, or parents to worry very much about letting their kids play football .. . . until, 2002, when tau proteins indicating Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy were found in the brain of Mike Webster, the Hall of Fame center of the Pittsburgh Steelers, dead at the age of 50. Or rather, three years later, when the pathologist who discovered CTE in Webster’s brain reported his findings in a medical journal. Or rather, four years after that, when to Alan Schwarz’s reporting in the New York Times since early 2007 on subsequent cases of CTE were added major stories in GQ and the New Yorker, and the general public, as well as Congress, became aware that football endangered not just hips, backs, and knees, but brains, too, with potentially devastating long-term consequences.

Uncritical acceptance of football’s necessary roughness has become no longer possible. But exactly how football will change is still playing out. American football is violent, has always been violent, and has always been loved and valued for its violence.

But now we know that football’s violence has more serious consequences than we ever imagined. Just how dangerous it is, to what portion of those who play it—not just in the NFL but at the high school and college and even youth-league levels as well—will remain uncertain until much more research can answer fundamental questions about the causes, duration, prevention, and long-term consequences of traumatic brain injury.

The current crisis over traumatic head injuries in football will not go away. In addition, while there’s still plenty of room for sensationalizing and posturing and imposing ideological biases in the media, at the heart of football’s current crisis is something real and unambiguous—those tau proteins in the brains of former NFL players who died demented, or by suicide after grotesquely erratic behavior; those lower scores on cognitive tests after a concussion in a high school football game.