At that time, “it was standard practice to exclude the black colleges from the national media, whether major newspapers or other publications about college life. For example, the anthologies of college songbooks published between 1900 and 1920 claimed to be all-inclusive, but the black colleges were not among the hundreds of institutions from all over the country that were represented. To study the “college life” of black colleges then, the first obstacle was that almost all the so-called colleges for black students around 1900 in fact offered little in the way of college-level instruction. Most were confined to elementary and secondary studies.

Second, the best-endowed colleges for African Americans—namely, Hampton Institute and Tuskegee—favored agricultural and industrial education to the neglect of collegiate studies. Not surprisingly, black college and professional school enrollments in the South were limited. According to a report by the U.S. Commissioner of Education, black college and professional school enrollments in the Southern states and Washington, D.C., totaled 3,880 in 1900. As a further indication of the paucity of educational opportunity, only 364 African Americans had earned college degrees in the Southern states and the District of Columbia.

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute was founded in 1868 by General Samuel Armstrong. He was interested in moral training and a practical, industrial education for southern blacks. In 1872, Booker T. Washington—who had born a slave in Virginia—arrived at the school with fifty cents in his pocket. After graduating, Washington was given administrative responsibilities at the school, and in 1881 Armstrong recommended Washington to head Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. By 1900, that school has numerous buildings, 100 faculty members, and more than 1,400 students.

Both Hampton Institute and Tuskegee Institute trained “an army of black educators,” and those teachers emphasized self-improvement and job training to enable black students to become gainfully employed and self-supporting as craftsmen or industrial workers. Armstrong and Washington accepted segregation as the natural inclination of both races. Washington considered immediate agitation for social equality to be “the extremist folly.”

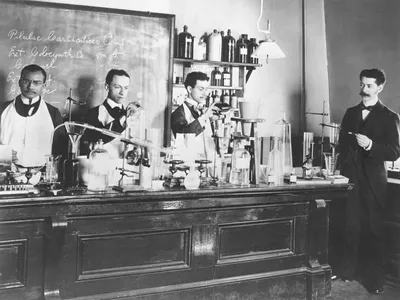

The trade school (Hampton Normal Institute) would offer instruction in farming, carpentry, harnessmaking, printing, tailoring, clocksmithing, blacksmithing, painting, and wheelwrighting. By 1904, nearly three-fourths of all boys at Hampton were taking trades classes.

(Last three paragraphs from Virginia Museum of History & Culture)

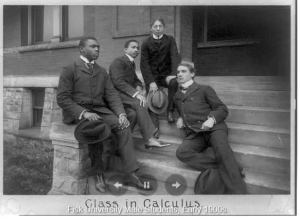

Two institutions were conspicuous for offering a liberal arts college education to black students: Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Fisk University in Nashville. These distinctive institutions were characterized by high morale and a strong commitment on the part of students and alumni to providing a highly educated leadership. Lacking endowments and dependent primarily on the contributions of black missionary groups and church associations, Howard and Fisk deliberately set themselves apart from the industrial-vocational model of Hampton and Tuskegee. Yet they paid a high price for this high purpose: they did not become objects of support from Northern foundations or what was called industrial philanthropy. Accounts of student life at these institutions are scant, but most indicate a seriousness of purpose among faculty and students, with little time or money available for the activities associated with the self-indulgent “collegiate way” of Yale and Dartmouth.

Gradually, however, Fisk and Howard forfeited some of their autonomy and mission as their boards came to be filled by candidates championed by the national foundations and the Rockefeller General Education Board. This change brought substantial endowments and resources to the underfunded colleges. It also brought Fisk and Howard increasingly into the fold of emulating the “college system” from elsewhere. As W.E. B. DuBois concluded in a commencement address at Howard University in 1930, “Our college man today is, on the average, a man untouched by real culture. He deliberately surrenders to selfish and even silly ideals, swarming into semiprofessional athletics and Greek letter societies, and affecting to despise scholarship and the hard grind of study and research. The greatest meetings of the Negro college year like those of the white college year have become vulgar exhibitions of liquor, extravagance, and fur coats. We have in our colleges a growing mass of stupidity and indifference.”” From John Thelin’s History of American Higher Education

W.E.B. Dubois’ Commencement Speech to Howard University graduates in 1930 (pertaining to his concerns with black students focusing too much on selfish ideals learned from white students who do not have to think as much in college.)