Fascinating piece by Tristan Ahtone and Robert Lee about where the land for the creation of land-grant colleges came from. It was double this length – I cut it down the parts I found most interesting.

Analogy

“Try this scenario, devised by Cutcha Risling Baldy (Hupa/Yurok/Karuk) as a way for her students to better envision the dilemma. She’s the department chair of Native American studies at Humboldt State University in California.

Imagine this: Your roommate’s boyfriend comes in one day and steals your computer. He uses it in front of you, and when you point out it’s your computer, not his, he disagrees. He found it. You weren’t using it. It’s his.

“How long until you can let that go?” she said. “How long until you’re like, ‘Never mind, I guess that’s your computer now.’ ’’

Now imagine that’s what happened to your land. “How long are we supposed to not say, ‘This is the land that you stole, so you don’t get to claim ownership of it, and then feel really proud of yourself that you’re using it for education?’ ’’ Baldy said.”

Now the boyfriend of your roommate feels bad about taking your computer. He has an idea: What if he put a plaque on it that says it belonged to you? That way every time he uses it, everyone will know that it used to be your computer. It will be his formal acknowledgement that it used to be yours.

How would you feel about that?”

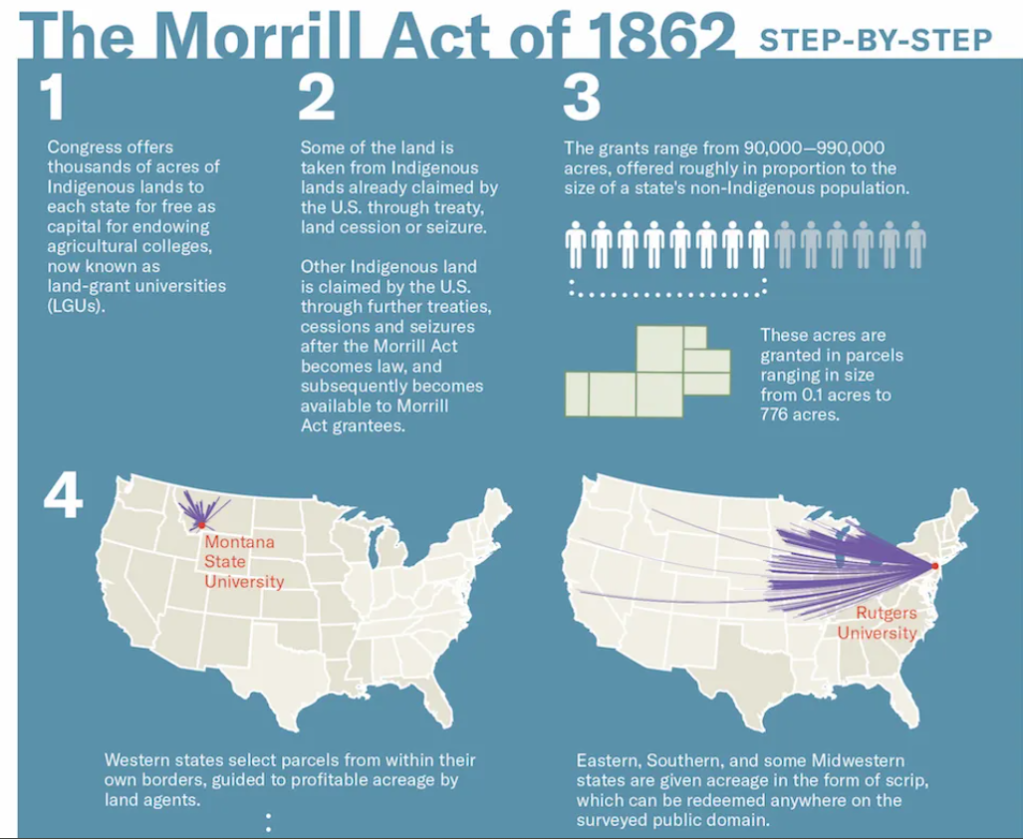

“In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act, which distributed public domain lands to raise funds for fledgling colleges across the nation. Now thriving, the institutions seldom ask who paid for their good fortune. Their students sit in halls named after the act’s sponsor, Vermont Rep. Justin Morrill, and stroll past panoramic murals that embody creation stories that start with gifts of free land.

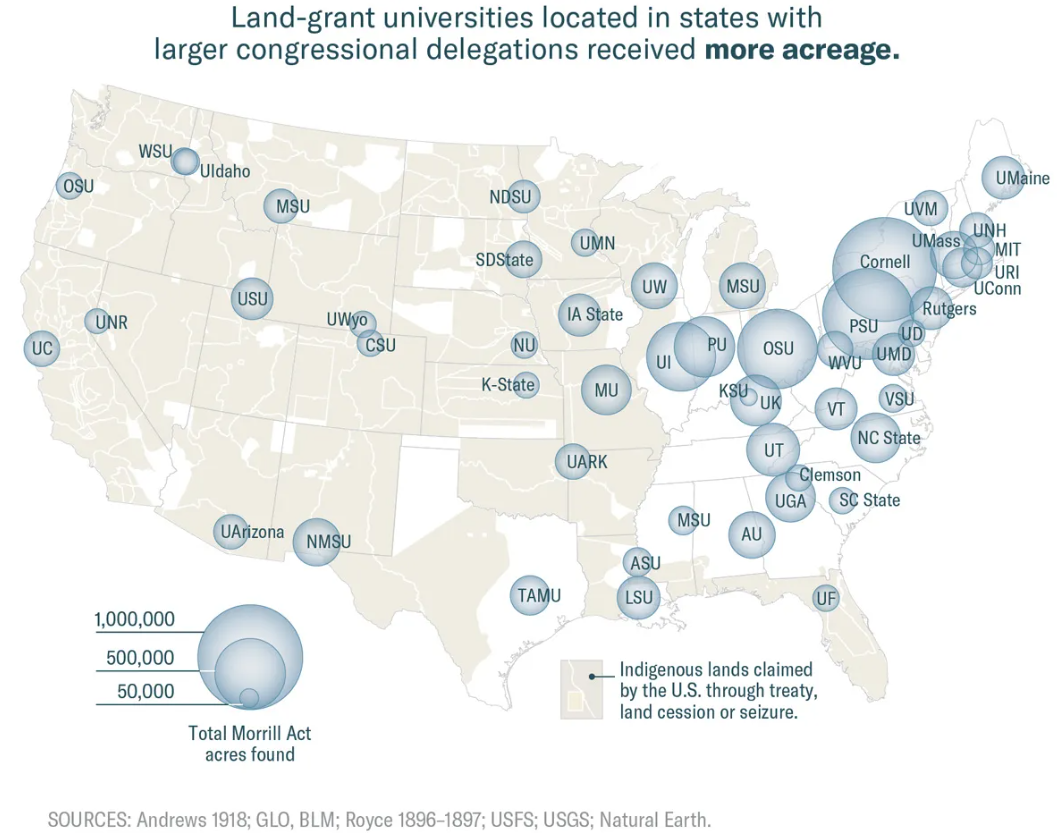

Behind that myth lies a massive wealth transfer masquerading as a donation. The Morrill Act worked by turning land expropriated from tribal nations into seed money for higher education. In all, the act redistributed nearly 11 million acres — an area larger than Massachusetts and Connecticut combined. But with a footprint broken up into almost 80,000 parcels of land, scattered mostly across 24 Western states, its place in the violent history of North America’s colonization has remained comfortably inaccessible.

We reconstructed approximately 10.7 million acres taken from nearly 250 tribes, bands and communities through over 160 violence-backed land cessions, a legal term for the giving up of territory.

High Country News has located more than 99% of all Morrill Act acres, identified their original Indigenous inhabitants and caretakers, and researched the principal raised from their sale in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We reconstructed approximately 10.7 million acres taken from nearly 250 tribes, bands and communities through over 160 violence-backed land cessions, a legal term for the giving up of territory.

The returns were stunning: To extinguish Indigenous title to land siphoned through the Morrill Act, the United States paid less than $400,000. But in truth, it often paid nothing at all. Not a single dollar was paid for more than a quarter of the parcels that supplied the grants — land confiscated through outright seizure or by treaties that were never ratified by the federal government. From the University of Florida to Washington State University, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to the University of Arizona, the grants of land raised endowment principal for 52 institutions across the United States.

Contemporaries not only welcomed the grants as “a very munificent endowment,” they competed to acquire them to found new colleges or stabilize existing institutions. The money provided interest income, inspired gifts and boosted local economies, which is why a 2014 study called it “the gift that keeps on giving.”

Altogether, the grants, when adjusted for inflation, were worth about half a billion dollars. In California, land seized from the Chumash, Yokuts and Kitanemuk tribes by unratified treaty in 1851 became the property of the University of California and is now home to the Directors Guild of America.In Missoula, Montana, a Walmart Supercenter sits on land originally ceded by the Pend d’Oreille, Salish and Kootenai to fund Texas A&M. In Washington, Duwamish land transferred by treaty benefited Clemson University and is now home to the Fort Lawton Post military cemetery. Meanwhile, the Duwamish remain unrecognized by the federal government, despite signing a treaty with the United States.

“Unquestionably, the history of land-grant universities intersects with that of Native Americans and the taking of their lands,” said the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities in a written statement. “While we cannot change the past, land-grant universities have and will continue to be focused on building a better future for everyone.”

On July 2, 1862, Lincoln signed “An Act donating Public Lands to the several States and Territories which may provide Colleges for the Benefit of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts.” Contemporaries called it the Agricultural College Act. Historians prefer the Morrill Act, after the law’s sponsor.

The legislation marked the federal government’s first major foray into funding for higher education. The key building blocks were already there; a few agricultural and mechanical colleges existed, as did several universities with federal land grants. But the Morrill Act combined the two on a national scale. The idea was simple: Aid economic development by broadening access to higher education for the nation’s farmhands and industrial classes.

The original mission was to teach the latest in agricultural science and mechanical arts, “so it had this kind of applied utilitarian vibe to it,” said Sorber. But the act’s wording was flexible enough to allow classical studies and basic science, too. With the nation in the midst of the Civil War, it also called for instruction in military tactics.

The first to sign on for a share of the Morrill Act’s bounty was Iowa in 1862, assigning the land to what later became Iowa State University. Another 33 states followed during that decade, and 13 more did so by 1910. Five states split the endowment, mostly in the South, where several historically Black colleges became partial beneficiaries. Demonstrating its commitment to the separate but equal doctrine, Kentucky allocated 87% of its endowment to white students at the University of Kentucky and 13% to Black students at Kentucky State University.

Not every state received land linked to the Morrill Act of 1862. Oklahoma received an agricultural college grant through other laws, located primarily on Osage and Quapaw land cessions. Alaska got some agricultural college land via pre-statehood laws, while Hawai‘i received a cash endowment for a land-grant college.

Pennsylvania State University’s 780,000-acre grant, for instance, came from the homelands of more than 112 tribes, including the Yakama, Menominee, Apache, Cheyenne-Arapaho, Pomo, Ho-Chunk, Sac and Fox Nation and Klamath. The land was acquired by the United States for approximately $38,000 and included land seizures without compensation. The windfall netted Penn State more than $439,000 — about $7.8 million, when adjusted for inflation. Penn State’s grant is connected to 50 land cessions cast across 16 states.

“As far as the modern institutions that you know, obviously, that funding is kind of a drop in the bucket of the operation of these institutions,” said Nathan Sorber. “But at the time, the reason they’re here, the reason they were able to weather the difficult financial times of the 19th century, was because of that initial land.”

In many places, the return for Indigenous title is incalculable because nothing was paid for the land. Often, however, the extraordinary boon to universities remains clear: Morrill Act funds were the entire endowment of more than a third of land-grant colleges a half-century after the law’s passage.

Such was the case for the University of Arkansas. Founded as Arkansas Industrial University in 1871, the institution benefited from almost 150,000 acres of scrip sold for $135,000 in 1872. More than 140 tribal nations had received just $966 for the same land. Behind the stark disparity lie hundreds of pieces of scrip redeemed in California, where Indigenous communities were hunted and exterminated.

Bounties for Indigenous heads and scalps, paid by the state and reimbursed by the federal government, encouraged the carving up of traditional territories without any compensation. Meanwhile, 18 treaties made to secure land cessions were rejected by the Senate and kept secret for a half-century by Congress.

“It’s called genocide,” admitted California Gov. Gavin Newsom, D, last year when he issued a formal apology for the “dispossession and the attempted destruction of tribal communities.”

Thirty-two land-grant universities got a share of California Indian land, raising approximately $3.6 million from over 1.7 million acres. Among them one finds far-flung scrip schools like Virginia Tech, Louisiana State University and the University of Maine.

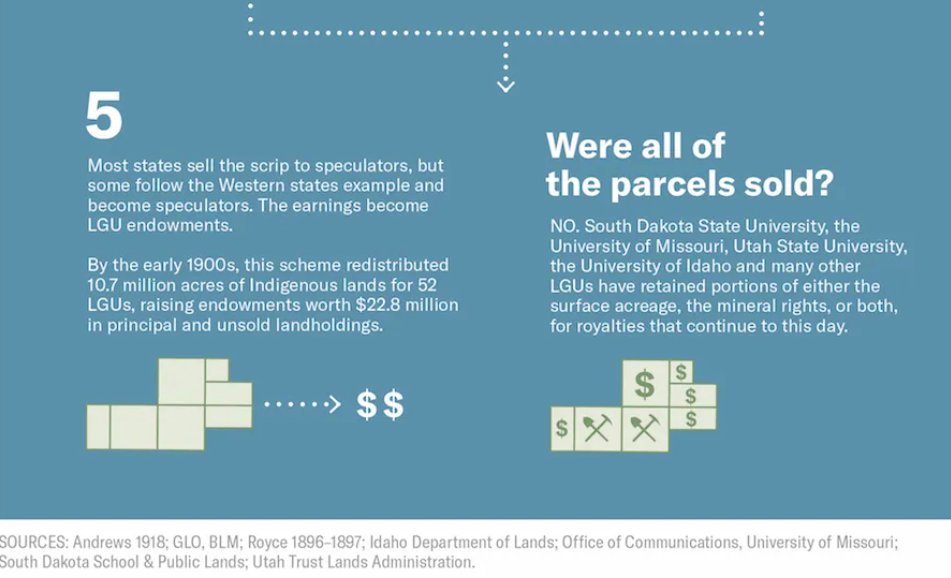

Still Cashing In

It remains impossible to determine who raised the largest endowment principal from the Morrill lands, because not all those lands have been sold. While most scrip-states offloaded their land quickly, Western states tended to hold on to it longer, generating higher returns. There was never a deadline to sell.

Idaho, for instance, still manages an area larger than Manhattan — claimed by the United States through an 1863 treaty rejected then, and now, by the Nez Perce — for the benefit of the University of Idaho. With over 33,000 acres of its 90,000-acre grant left unsold, as well as another 70,000 acres of mineral rights, the university generated more than $359,000 in revenue in fiscal year 2019 alone.

Montana State University still owns almost twice as much land as Idaho does, taken from the Blackfeet, Crow, Salish and Kootenai, Nez Perce, Colville and Ojibwe. In fiscal year 2019, MSU made more than $630,000 from its approximately 63,000 remaining Morrill Act acres.

Meanwhile, Washington has retained nearly 80% of the original grant to fund Washington State University. No money was paid by the federal government to the Coeur d’Alene, Colville, Shoalwater Bay and Chehalis tribes for land supporting WSU. The Makah, Puget Sound Salish, Chemakuan, S’Klallam, Umatilla and Yakama received a combined $2,700 for their land cessions. In fiscal year 2019, the remaining lands generated $4.5 million for WSU, mostly from timber harvests.

This is what we know: Hundreds of violence-backed treaties and seizures extinguished Indigenous title to over 2 billion acres of the United States. Nearly 11 million of those acres were used to launch 52 land-grant institutions. The money has been on the books ever since, earning interest, while a dozen or more of those universities still generate revenue from unsold lands. Meanwhile, Indigenous people remain largely absent from student populations, staff, faculty and even curriculum.”