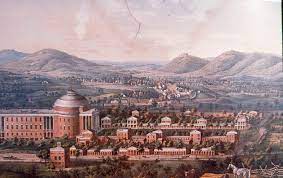

“The University of Virginia, “Mister Jefferson’s University,” stood out as a model and marvel of planning, in both its educational mission and its architecture. Its greatness is in large measure a function of its distinctiveness. It was a counterpoint to conventional thinking and presumptions. The famous “academical village” and such well-designed buildings as the Rotunda provided the setting for an innovative curriculum that eschewed the usual nomenclature of academic classes, degrees, and course requirements. At the University of Virginia, courses of study included modern languages, science, and architecture. Faculty were hand-picked, coming from international universities as well as leading American institutions. There was no daily chapel and no links to religious denominations.

Students were to be full citizens in a self-governing community. The conventional system of demerits and petty rules of discipline was supplanted by a unique student code- -a code that was literally by and for students. Faculty received explicit instructions that being a professor was to be their sole and total commitment. The vision projected by the impressive architectural and curricular plans, however, overshadowed the realities of living and learning at the new University of Virginia. Even Jefferson acknowledged this fact.

Some of the disappointments were prosaic, predictable, and relatively unimportant. For example, Jefferson had envisioned a combination of living and learning that would combine the study of foreign languages with immersion in the cultures of other nations, including their cuisine. This idea never really reached fruition, and cooking as well as conduct tended to remain in the realm of regional rather than cosmopolitan habits. It was acceptable to have some familiarity with the classics, modern languages, and the liberal arts, but serious scholarship or any intense commitment beyond the scope of a gentleman’s life received little encouragement within the student culture.

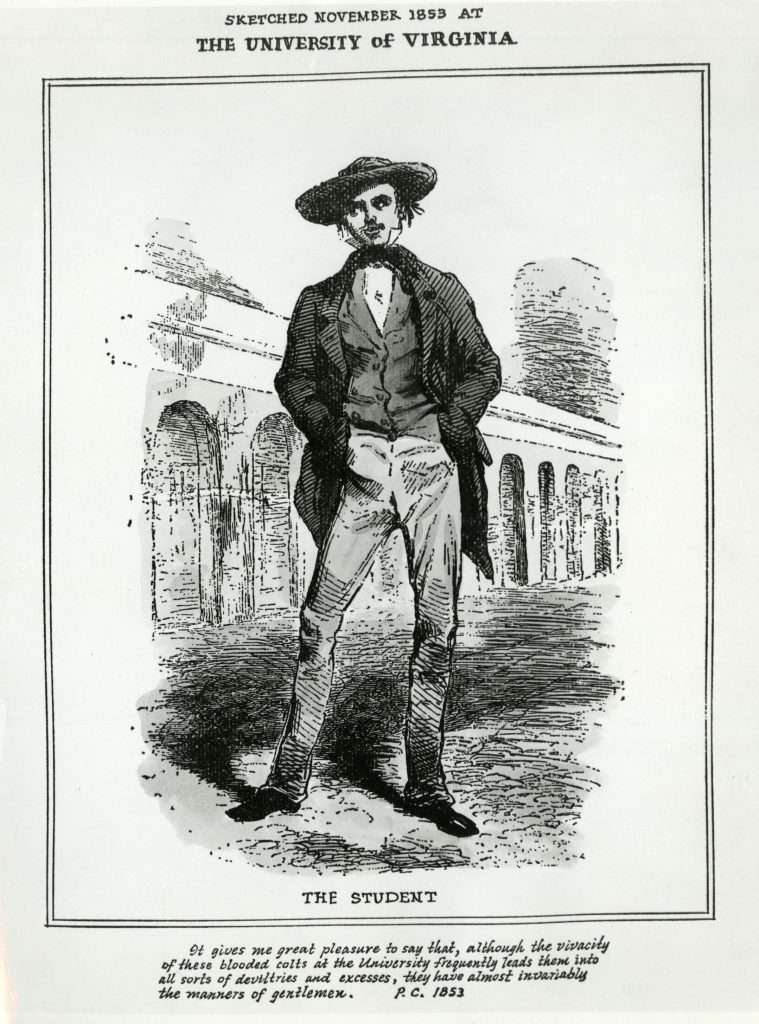

The gap between the ideal and the reality of the new University of Virginia was due in large measure to the conduct of its students. The students, like their counterparts at South Carolina College, were overwhelmingly drawn from wealthy planter families in Virginia and other Southern states. Tuition was the highest of any university in the country, which added a financial obstacle to the strong social class tracking that was in place–a peculiar feature in light of Jefferson’s professed commitment to an “aristocracy of talent.”

A gravitation toward regional and provincial elitism rather than toward genuine merit and international or neoclassical norms was evident in student attitudes, values, and conduct. Virginia’s students were the sons of a landed gentry, and they brought with them to Charlottesville their slaves, servants, and horses and their fondness for drinking, gambling, and guns. Faculty were essentially powerless to discourage such pastimes.

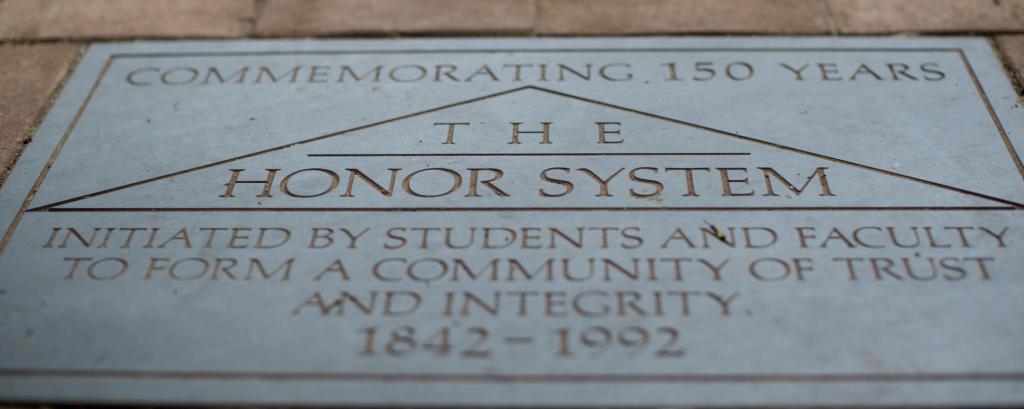

Because Jefferson had allowed students such great powers of self-determination, the University of Virginia’s early decades were shaped by a code of honor that had few checks or balances. It was considered appropriate for students to challenge professors, to take umbrage at alleged insults by faculty. And, most important, the student code defined academic citizenship in a peculiar, wrong-spirited way: “honor” meant never betraying a fellow student – hardly a spirit conducive to promoting the highest values of a university.

It would be fair to say that by 1860 the University of Virginia had become successful at transmitting the distinctive code and culture of the nineteenth-century Virginia gentleman to its students, and to the souls of future leadership. Whether this educational success included fostering an aristocracy of talent as envisioned by Thomas Jefferson is dubious at best.”

From Thelin’s History of American Higher Education