“Seventy years ago, before conference realignment was all the rage, UVA was the Atlantic Coast Conference’s first expansion target.

On Oct. 9, 1953, the Board of Visitors met to consider whether to join the new league, an offshoot of the Southern Conference formed five months earlier.

The vote was 6-4, a narrow margin that went against the recommendation of President Colgate Darden (Col 1922). Rector Barron Black (Col 1917, Law 1920) also opposed it.

The minutes of the meeting provide a window into the thinking at the time, much of it familiar to modern fans. The debate centered on issues that still resonate: the role of athletics at a university, the growing commercialization of college sports, and the balancing act involved in competing at the highest level without compromising academic standards or breaking rules.

Alumni sentiment was split, with “rabid people on each side,” reported Hunter Faulconer (Col 1930), president of the Alumni Association. The Association’s Board of Managers had discussed ACC membership at the time but took no vote. “You will be severely criticized, whatever you do,” Faulconer said, by way of reassurance.

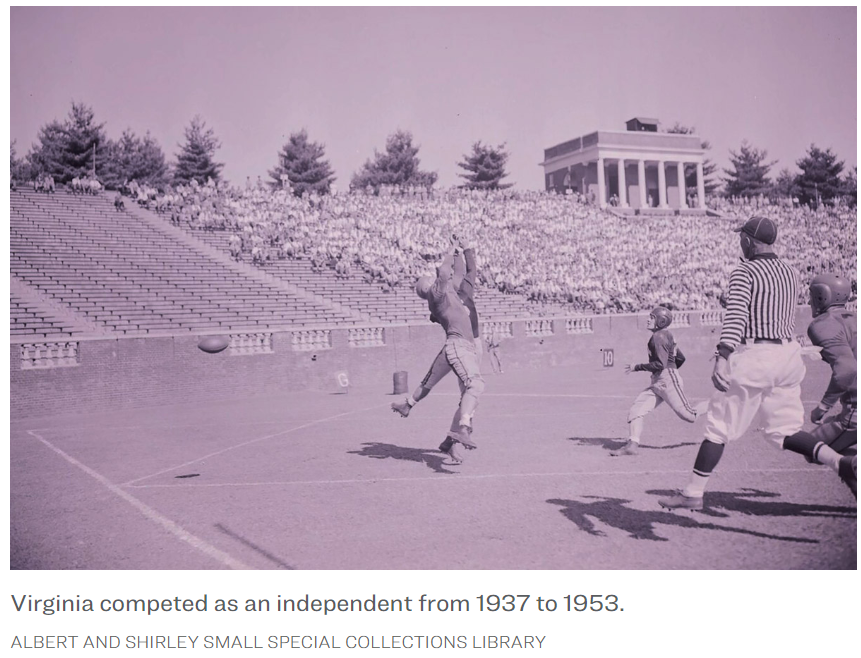

It was no easy call. UVA had been competing as an independent since leaving the Southern Conference in 1937, and there was general satisfaction with the status quo. UVA left the Southern Conference in large part because it wanted to offer athletic scholarships, which were forbidden by conference rules but widely known to be given under the table. It put UVA at a disadvantage, school officials believed, because while its students had to sign a pledge, on their Honor, saying they received no aid, other universities had no such requirement. “Our athletics are commercialized whether we like it or not.”—Board of Visitors member Frank Talbott, in 1953

Going it alone had allowed UVA to offer scholarships on the up-and-up. It also enabled the University to schedule like-minded schools, including some from the Ivy League. Now the University was considering realigning with some of the same schools—the same bad actors, in its view—that it had left behind in the Southern Conference.

To the University rector, a Norfolk lawyer, that made no sense. “If we join, we will be returning to exactly the same situation we withdrew from in the Southern Conference,” Black said. “Rules will be laid down; we will obey them, others will violate them.”

Board of Visitor Thomas Benjamin Gay (Law 1906) echoed that sentiment. “Should we sit down with a group that will violate any rules we adopt?” he said. “I am opposed to any such conference.”

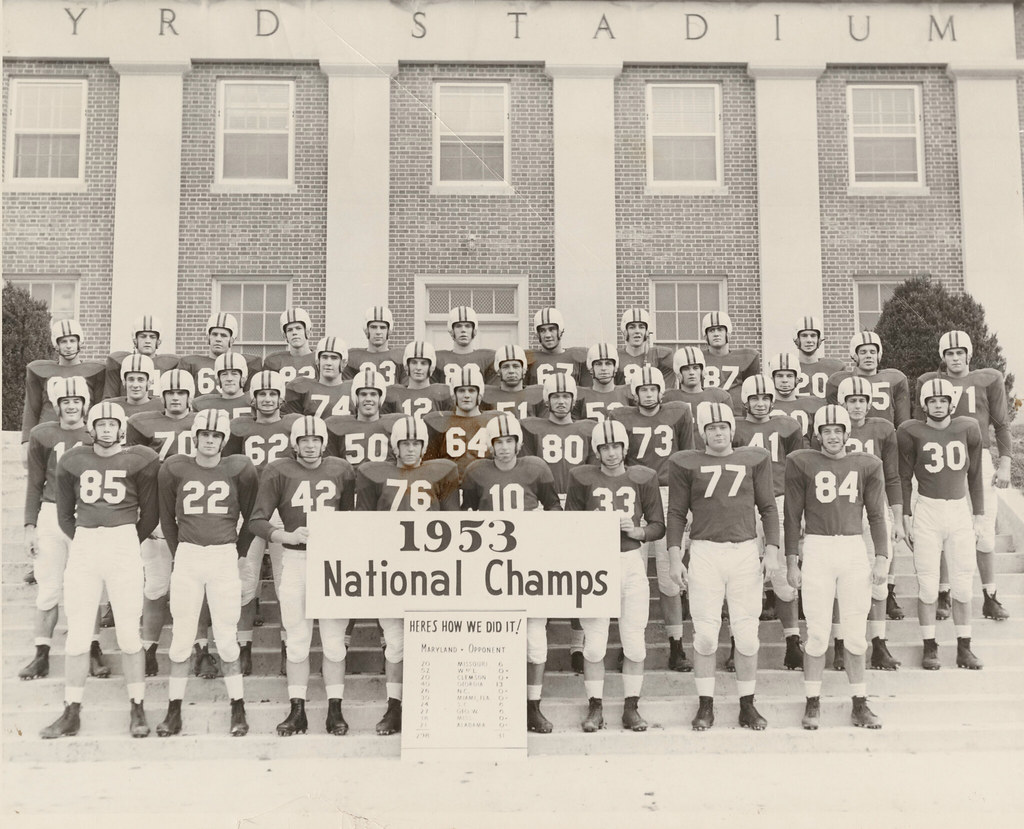

The chief target of the insinuations had a name: the University of Maryland, a national football power in the early 1950s. When the Southern Conference voted in 1951 to ban its members from participating in bowl games, citing gambling and financial scandals, Maryland played in the Sugar Bowl anyway. (Clemson, also defiant, played in the Orange Bowl. Unhappiness with the bowl ban was a major reason those schools, and five others, left the Southern Conference and formed the ACC.)

UVA leaders viewed Maryland’s football success with suspicion, its sense of institutional priorities with contempt. The Maryland and Washington alumni chapters, some of those rabid fans Faulconer referenced, vehemently opposed joining any league that included the hated Terrapins.

“In the opinion of our alumni groups, Maryland will violate ACC rules?” Black asked. “Yes,” Faulconer said. “What about other schools?” Black asked later. “Wake Forest for example?” The critics “never get that far,” Faulconer said. “They stop at Maryland.”

Others predicted that some schools would lower academic standards to win, putting UVA in an untenable position. Nelson T. Offutt (Col 1933), president of the Student Aid Foundation, rattled off the suspects: Maryland, Wake Forest, Duke, North Carolina State.

It would be a “psychological disadvantage” to be at the bottom of such a conference, Offutt said. “How will we get players?”

For his part, after “long and careful consideration,” Darden advocated remaining independent. He did not want to alienate the Maryland and Washington alumni chapters, he said. He was also concerned that by joining the ACC, UVA would separate itself from other state schools.

Last, Darden opposed a proposed ACC rule that required athletes to pass 12 credit hours to remain eligible. UVA required just nine. Given the school’s high academic standards, adding three more hours would burden athletes, he said. Football players would leave.

On the other side were those making a case also familiar to modern fans. They urged UVA to get with the times, so to speak, and accept the then-new realities of college sports. Gus Tebell, the director of athletics, said scheduling would become more difficult the longer UVA stayed independent. Duke, a longtime rival UVA had continued to play, told Tebell it would no longer schedule the Cavaliers unless they joined the ACC. North Carolina might follow suit. Even Ivy League teams were looking for “big-money” teams to play outside their league games, Tebell said. Scheduling for sports other than football would also grow more difficult, he warned.

Visitor Frank Talbott (Col 1921, Law 1924) reminded the board that the athletics department was self-sustaining. If UVA was unable to schedule teams fans wanted to see, financial support would dry up, he said. “Our athletics are commercialized whether we like it or not,” he said.

Talbott and Mortimer Caplin (Col 1937, Law 1940), a law school professor who chaired the athletics council, a seven-member advisory board, said that getting in on the ground floor of the ACC would give UVA a seat at the table when rules and regulations were formed. Duke and North Carolina were sympathetic with UVA’s concerns and wanted the school’s backing in setting policy, Talbott said.

Membership in the Southern Conference had been like Prohibition, Talbott said. A nominal ban, widespread violations. The ACC would be different. “The ACC approach is an admission of evils and a plan for their control,” he said. “Our influence will be great.”

What of UVA’s archenemy to the north? Tebell said that although Maryland’s “recent ruthless attitude in building a football team” had turned sentiment against it, the schools competed in other sports and got along well. Added Caplin, who would go on to be commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service: “I don’t think we would be contaminated by one game a year.”

The arguments swayed none of the opponents of the move. The vote to join would have been closer had Gay not needed to leave before the meeting adjourned. Though it couldn’t be counted, he still asked that his nay be noted.

Visitor Bertha Pfister Wailes (Grad 1928, 1937), a professor at Sweet Briar College who voted no, also wanted to make a point, perhaps taken for granted but worth stating, nonetheless. “I hope the larger issues will not be lost sight of,” she said. “We should be mindful of the overriding importance of scholastic affairs, and our position in Virginia and in the country as an educational institution.”

This article was taken verbatim from Ed Miller in the UVA Magazine