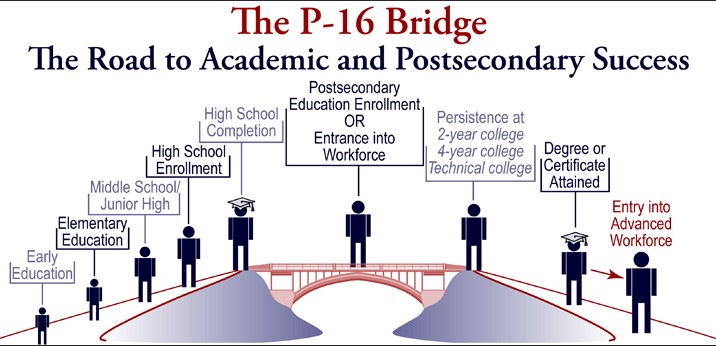

It was not until 1930 that the U.S. required all children to attend school from K-12. Thirty years ago another term emerged on the national consciousness, the “P-16” movement, which emphasized the importance of education for children from preschool through college. There has been progress on the rate of high school graduates going to college – in 1960, only 45% of high school graduates entered college, but today, high school graduates are entering college at closer to 70%.

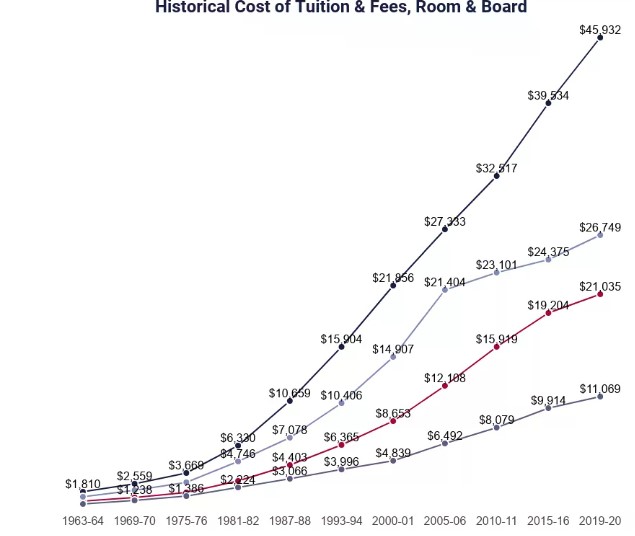

So our nation can argue that the jump from year 12 to year 13 has been significantly improved – although we would like it continue an upward movement. Unfortunately, unlike year 12, year 13 (college) is rarely free. The cost of college has been increasing at rates never before seen. Over the last forty years, the prices of private colleges have more than doubled and the prices of public colleges have almost quadrupled. Student debt in 1993 was under $10K per borrower and in recent years it has been nearing $35K per borrower.

In short, our nation is helping more high school graduates than ever go to college but students’ college debt is also at record levels. Add to this combination an awareness that with so many college graduates, simply getting a degree is no longer sufficient in many cases for a well-paying job.

Year 17

So what happens after the “P-16” investment in our youth ends? When students reach “year 17” at graduation, do employers line up at graduation to hand graduates full-time, well-paying jobs? This is rarely the case. If jobs post college are not simply handed out, who helps college graduates find jobs?

For starters, it is not the faculty. Believe it or not, college faculty are not required to have any coursework on how to teach in college; neither do they have any training on how to help students find jobs. In fact, many faculty have only interviewed for one job in their lives, the one that they earned after completing their graduate degree, and that was a job to keep them at a college the rest of their working lives, never entering the world of work outside of college.

A dirty little secret of higher education is that faculty members at most American colleges and universities have never taken a course on how to teach.

Thankfully, as college graduates are having to compete more for jobs, an entire profession of college career/placement counselors has risen up. These career counselors originally emerged from the counseling profession, and for decades, if not even today, many of them focused more on counseling and guiding students through an exploration of their future. There was an expectation that these staff would provide soon-to-be graduates with the resources to effectively conduct a successful job search, not an expectation that that these staff were responsible for placing graduates in jobs.

What Are Colleges Sharing About Placement Data?

It was noteworthy then, only eight years ago, that the national organization for career professionals (NACE) provided guidelines for how colleges should measure and document college student placement rates. These are guidelines, not requirements, and as of 2020, the most recent year data is available, only 337 four-year colleges out of the 2,679 bachelor’s degree granting colleges in the U.S. submitted their placement data to NACE. This is just over 12% of all the four-year colleges in the nation sharing their college placement rates with the national organization tracking this data. Sadly, these 337 universities are missing information on what 42% of their students are doing after graduation.

Of the 58% of graduates for whom these colleges have data, 82% of the students have reached a goal termed “career success.” NACE defines “career success” as “the percentage of graduates who fall into the following categories: 1) Employed full time, 2) Employed part time, 3) Participating in a program of voluntary service, 4) Serving in the U.S. Armed Forces or 5) Enrolled in a program of continuing education.”

Based on this definition, “career success” includes college graduates working 40 hours/week as a plumber’s assistant, 30 hours/week at McDonalds, or even 15 hours/week at a carwash. How many parents (or students) would argue that “career success” post-graduation would be job that requires no college education and potentially pays minimum wage? The reality is that “career success” often means that college graduates are doing work they could have done at the age of 16, without even a high school degree.

An Analogy

Imagine you have cancer, and you go to the doctor to be cured. The doctor tells you that the treatment will cost you thousands of dollars, even if you have medical insurance. Your future is very important to you, so you ask the doctor about the odds of success. The doctor responds by saying that the medical community has data on cancer survival rates from 12.5% of the hospitals in the U.S., and of these hospitals that are treating cancer patients, we know what happened to 58% of these patients.

Fortunately, of this group of people (7.25% of cancer patients in the U.S.), we have records indicating that 82% of them succeeded in their treatment. When you ask what treatment success means, the doctor explains that the definition of being healed means your life could be much better, but that the 82% of successful treatments includes results that in a quality of life at, or below, your life pre-treatment. How confident are you that this treatment is worth it?

As an aside, my friend and distinguished colleague, Kevin Dougherty, reminded me, the 18% who have not achieved “career success” according to NACE (placement within 6 months), may include stay-at-home parents or other care-givers. I admit I am only focusing on the stated definition of NACE’s and the federal government’s definition of “career success.” College is much more than this for many, including me; but these other outcomes are less tangible and less compelling to most families paying for college.

A Sampling of Colleges Sharing Their Placement Data

Needless to say, in spite of NACE’s efforts to improve the tracking of college graduates’ career outcomes, only a small percentage of colleges are currently willing to participate. In effort to sample some more well-known colleges, I selected the Power 5 Conferences, because fairly or not, they get the bulk of attention from prospective students. All of them are over 5,000 students. However, I also threw in the Ivies, since they too, get so much national attention. I counted the number of schools submitting data in both 2019 and 2020 and combined the number unique schools participating in that conference to come up with the overall participation percentage.

Some colleges only provided data from either their School of Business (B) or Engineering (E). This is more common because business and engineering schools include majors that are more attractive to employers. For the purposes of my analysis, institutions that submitted just a School of Business or Engineering, received 1/3 credit, a generous assessment since business and engineering graduates typically make up 20% and 5% of college graduates in a given year. No school had both the Schools of Engineering and Business submit data so fractions represent multiple universities submitting partial data (.9 = 3 colleges). However, the .8 total for the entirety of the Power 5 represents 6 colleges submitting either just their School of Business or Engineering.

| Conference | # in Conf. | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 + 2020 | % of Conference |

| ACC | 15 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 49% |

| Big 10 | 14 | 7.3 | 5.6 | 7.6 | 54% |

| Big 12 | 10 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 6.6 | 66% |

| PAC 12 | 12 | 5.3 | 7 | 7.3 | 61% |

| SEC | 14 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 64% |

| Power 5 | 65 | 36 + 6 partials | 55-65% | ||

| Ivy | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 50% |

(If you want to know if a certain college participated in 2020, you can find that list on pages 124-131 of the NACE First Destinations Report. For 2019, you can find that list on pages 32-40 of the 2019 NACE report.)

In light of the fact that only 12.5% of the 4-year colleges in the nation are voluntarily submitting their students’ placement data, these results come as a pleasant surprise. If we are only counting Power 5 universities submitting their overall placement data, 55% of the colleges are participating. If we count partial submissions as institutional participation, we could say 65% are participating. Of the eight Ivies, three of the four colleges submitted their placement data, and three of the four included the top three ranked Ivies; Harvard, Princeton, and Yale (Penn is the fourth). Another perspective is that only a little over half of some of the most well-known and large universities in the nation are choosing to share their graduates’ success.

Reasons for Attending College Have Changed

In the 20th century, colleges often talked about their outcomes being focused on developing an appreciation for learning and becoming a more responsible citizen. But raising tuition dramatically impacts the public trust and results in different priorities for families. Since 1971, there has been a 25% increase in the number of students going to college to make more money. In the lower paying K-12 teaching profession, in 1966, 23.3% of students were seeking to be teachers. In 2019, this number had dropped to 4.5%.

But what if colleges decided to do more than the minimum, and identified graduates in positions that would not have been possible without graduating from college? What if colleges identified the number of their graduates who are underemployed or only in part-time roles? Many of these colleges have this data – but they are not publicly sharing it. Personally, I think it is time that families started holding college’s career placement offices to a higher standard. Sadly, I think parents are of the mindset that their child’s college degree will open doors for them with little or no effort on their child’s part. This is not the case and I suggest families begin to hold colleges accountable for their promised results.

(In my next article, Why Don’t Universities Follow Federal Law To Document Post-Grad. Success?, we will examine the federal requirements that colleges must share placement rates and the surprising number of colleges failing to do this.)

More data demonstrating these issues can be found here –