What do the following companies have in common: General Electric, Disney, Microsoft, Netflix, Airbnb? They share the same thing in common as Texas A&M, University of Michigan, University of North Carolina, Georgetown University, and Brigham Young University. All these companies and universities were founded in the middle of an extended recession. These are just a few of many examples. I wonder what great companies and colleges are getting their start during the COVID recession?

Many new organizations (and many adaptable current ones) will start doing some things different as this crisis continues. One of the most significant changes will be the use of video to broadcast great teaching and stimulate increased learning.

Great Teaching Pre-Internet

At the University of Virginia, where I attended college, I was able to see great lecturers. Albeit, I was packed into lecture halls of 300-500 students, but the performances I observed were memorable. I saw Francis Carey teaching organic chemistry from the book he wrote, which most colleges in the nation were then using. I listened to Ken Elzinga teach economics by telling parables and having us read engaging fiction novels he had a written to subtly teach economic concepts (see picture below).

I heard and watched James Childress teach Theology, Ethics and Medicine, based on the seminal book he had written. In class, he would describe real-life examples of when he had been called to consult on doctor’s and patients’ life or death decisions. Taking these professors classes in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s was the equivalent of watching weekly TED talks.

There were also many other teachers who lectured and were not effective. These were often brilliant researchers who were focused on ground-breaking new knowledge which could alter the course of human history but had never been taught how to teach. In college, I learned don’t take classes with interesting titles, take classes with interesting teachers. Some of my most boring classes were titled and described in a fascinating manner, and some of my most powerful learning experiences came from a teacher for a class that sounded mundane in the catalog.

Learning to Teach

When it finally came time for me to teach my first class, in my mid-20’s, I was petrified. There was no way I could replicate the masterful lecturing I had been able to experience in college and there was no way I wanted to be like the professors we all complained about. I was going to be the guy no one wanted to take because he barely knew what he was doing – but we all have to start somewhere.

At first, I tried to write out my lectures but that tied me to my notes and was less engaging for the students. Then I tried to speak extemporaneously in an engaging way but I would eventually end up in silence when I had nothing else to say and was not sure what to do. I tried to include humor but I have never been good at remembering jokes so I would forget key parts. Even when I put my all into what became a great lecture, I had to spend hours writing it, memorizing it, and practicing the performance. In short, I quickly learned that I probably not become a great lecturer.

While I knew I would not be the person who could regularly rally a room around an important topic with my words I still wanted my students to be able to experience moving talks in the classroom. Fortunately, the 1990’s were an era where VCRs had emerged as a popular communication tool and I learned that movie clips of great scenes were an excellent alternative. My students could learn from Gene Hackman in Hoosiers, Tom Cruise in A Few Good Men, Morgan Freeman in Shawshank Redemption, Tom Hanks in Saving Private Ryan, Michelle Pfeiffer in Dangerous Minds, Denzel Washington in Remember the Titans, or one of my favorite actors, Robin Williams, in Dead Poet’s Society or Good Will Hunting.

It was not an easy set up back then, I had to buy or rent the tapes, check out a VCR and TV, cue up the key moment, and hope the sound on the TV was loud enough. But it was worth it. Showing one good movie clip could lead to an excellent discussion for the remainder of class. Seeing a powerful performance energized the class and almost transferred the clip’s passion into the discussion. It is hard to play it cool when Coach Boone tells his players, on the Gettysburg battle site, that they must come together and play as a team to avoid a Civil War ever again.

In the 2000’s, advances in technology allowed me to try another approach to bringing great speakers into my class. I was teaching a course in a higher education master’s program. I reviewed the winners of the best presentations at professional conferences and identified great topics linked to top presenters. I reached out to them to see if they would be willing to share a shortened version of their recent conference talk with my class. In addition to shortening their often 45- to 60-minute presentations, they would need to download some software that would allow the class to see them (and them to see the class). The result was that we ended up with many of the best speakers on the topic in the nation, meeting with my students in Boone, North Carolina, where the closest airport was two hours away.

In the 2010’s, even better technologies emerged that allowed me to bring influential and powerful presenters to my classes. The introduction of TED talks in 2006 was a game-changer for me. One of the first six TED talks ever, “Do Schools Kill Creativity” by Sir Kenneth Robinson, became a talk I have shown almost all my students on or before our first day of class. (I actually use the version of it from a few years later that has been animated by RSA and gets to the meat of the matter a bit quicker.)

In recent years, I have been teaching a course on organizational behavior and leadership that lends itself quite easily to the use of TED talks on many of the topics we cover in class. There are other talks, outside of TED, that I and others also use, but the benefit of TED talks is that they are all 20 minutes or less – which has demonstrated to be the amount of time most students (and church-goers in my opinion) are willing to track with an engaging talk.

This short-attention span is based on multiple studies, but Donald Bligh’s 1971 book, “What’s the Use of Lectures?” helped many educators start to realize that “students’ attention spans and memory stamina vary widely so breaking the lecture into smaller increments of no longer than 20-30 minutes was optimal…” However, Bligh did not give up on the power of great speaker to influence as he stated that there could be “inspirational teachers whose lectures were so compelling they could hold student attention for hours.”

In the past few years, a group of researchers from MIT and EdX completed the largest study of video learning engagement. They used data from 6.9 million video watching sessions and discovered that “shorter videos are much more engaging, that informal talking-head videos are more engaging, that Khan-style tablet drawings are more engaging, that even high-quality pre-recorded classroom lectures might not make for engaging online videos.” In short, it had better be short and amazing to maintain attention. They shared several graphs showing that after six minutes of watching any speaker behind a podium, the drop off in viewer engagement was a steep trajectory down. Fortunately, TED talks can be sorted by a number of variables, and analysis of the most popular TED talks reveals that they are 12-14 minutes, have many viewer comments, are translated into many languages and obviously, have a high view count.

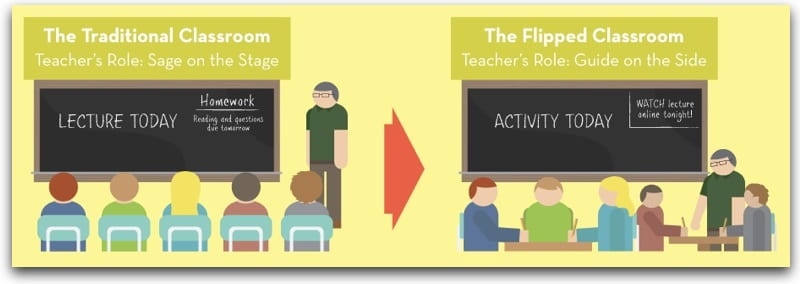

Another benefit of publicly available talks like TED talks is that students (and instructors) don’t have to spend time in class watching the videos. For the past several years, my students’ homework assignments are to watch at least one assigned video of a talk per week and to either discuss it in an online platform or in class. If you are saying to yourself that this concept sounds familiar, it should. This is the idea of flipping the classroom while “hiring” the best speaker on the topic to offer the out of class talk.

Flipping the classroom is more than a fancy term that sounds like a fad. Think about this – for over 2,000 years one of the primary methods of learning has been to be in the presence of someone who can teach (e.g. Socrates, Jesus, Gandhi). Now, with the advent of film and video, for the first time ever we can record great teachers and show them over and over. While we can’t go back and watch a Moses or Muhammed TED talk, for centuries going forward, anyone can watch MLK, JFK, or FDR.

What Do Multisite Churches, the Khan Academy, and Universities Have in Common?

While there are thousands of organizations trying to spread a message that have capitalized on this trend, let’s take a brief look at the multisite church movement. While they began in the 1990s, there are now thousands of multisite churches. How do they make this happen? Many, if not most, of them provide multiple “video venues.” Rick Warren, pastor of Saddleback Church, speaks by video to over 24,000 people at 15 locations in California and four international locations each Sunday. How does one pastor like Andy Stanley minister to his over 40,000 weekly church attendees? In short, he doesn’t. He has hundreds of staff members who facilitate thousands of small groups, Bible studies, Sunday School lessons, and affinity groups each week.

There is a parallel movement to multisite churches in higher education. One of the best examples is Coursera, a platform for online courses anyone can take. Some are free, and these are typically called MOOCs – massive online open courses), and some cost money.  Currently there have been over 2.6 million “students” in Coursera’s “The Science of Wellbeing” taught by Laurie Santos of Yale University. The class is ten weeks long and requires ~20 hours of work. Financial aid is available and course completers receive a Course Certificate. Coursera is one of many online learning opportunities. LinkedIn Learning, formerly Lynda, has become a major higher education partner and has many courses with hundreds of thousands students. Other top online course providers with thousands of students include: Udemy (50 million students and 57,000 instructors teaching courses in over 65 languages), Udacity (100,000 graduates), Khan Academy (5.7 million subscribers and 1.7 billion users,) and Codecademy (50 million users).

Currently there have been over 2.6 million “students” in Coursera’s “The Science of Wellbeing” taught by Laurie Santos of Yale University. The class is ten weeks long and requires ~20 hours of work. Financial aid is available and course completers receive a Course Certificate. Coursera is one of many online learning opportunities. LinkedIn Learning, formerly Lynda, has become a major higher education partner and has many courses with hundreds of thousands students. Other top online course providers with thousands of students include: Udemy (50 million students and 57,000 instructors teaching courses in over 65 languages), Udacity (100,000 graduates), Khan Academy (5.7 million subscribers and 1.7 billion users,) and Codecademy (50 million users).

These online course providers identify one of the best professors/teachers in the world on a topic and pay them to provide talks that walk learners through the content. Students in these programs are paying a fraction of the cost to take courses from educators significantly better at teaching than most college campus professors. For example, a Coursera course costs between $30-$100. The Khan Academy courses are always free! On the flip side, the cost of an average course at a public university is $1,000 and a private university is $3,000.

Let’s Not Have Another Yale Report of 1828

In the early 1800s, empirical and practical education were starting to find a place within higher education. However, in 1828, Yale University published an infamous report defending the classical curriculum and the necessity that all students learn Latin and Greek. Although Princeton, Harvard and many other colleges followed Yale’s lead, most higher education historians agree that the report set college curriculums back decades. It was not until the Morrill Act of 1862, when the federal government made its first major entrée into higher education, that incentives were designed to assure more modern curriculums.

In 2020, we are living during one of the greatest shifts in learning ever. We do not need another Yale Report defending the requirement that educated people are only those who experience face-to-face learning. How can we get universities to wisely incorporate more online learning? Reasons for this will be explored in my next article called “Why Colleges Must Adapt or Be Left Behind.”

Until then, let’s celebrate that greatest teachers of this generation can now be living anywhere in the world (with decent internet). Many of them are already on the internet teaching millions of students. Let’s use this unfortunate crisis as a building block for one of the best opportunities higher education has ever had to improve and expand student learning.

Robert,

Thanks for reading my blog and commenting. I hope you are doing well and enjoying the fall season.

Jeff

LikeLike